Trade Winds: How Global Businesses Are Navigating Trade, Tariffs, and the Uncharted Waters Ahead

Publication | 02.27.19

[ARTICLE PDF]

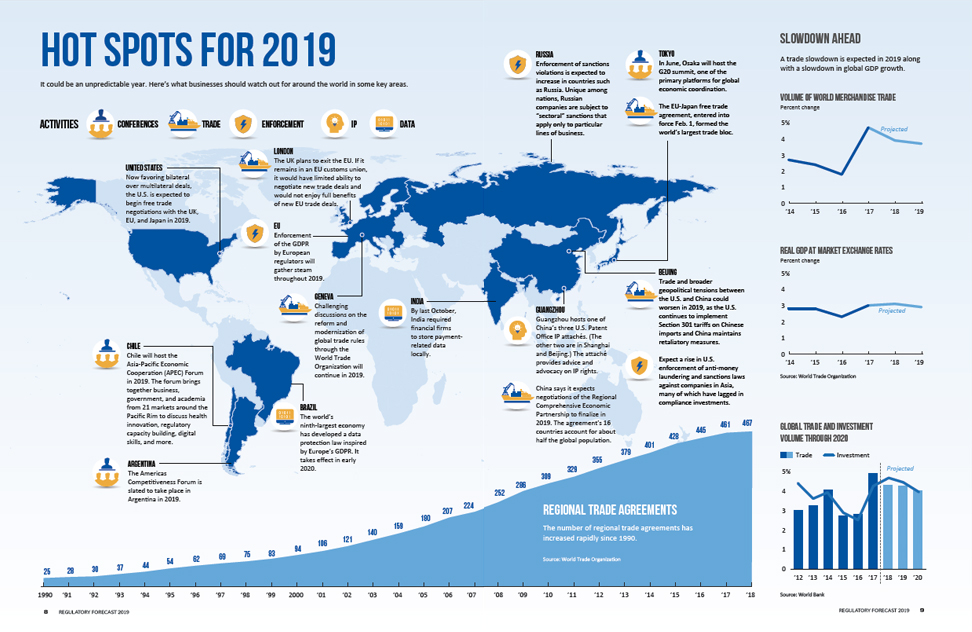

As we begin 2019, the global economy appears to be headed for uncharted waters, and many businesses are plotting a new course to avoid the storm clouds that could lie ahead. The global business climate is being challenged by mistrust and mercantilism. International agreements and organizations that have helped drive prosperity since World War II are fraying.

The Trump administration is advancing an “America First” agenda that is causing major companies to rethink everything from their supply chains to where they elect to site headquarters offices and major manufacturing facilities. Other countries are making bold changes to tariffs, privacy laws, and other regulations that will impact international trade. What is certain is that nearly every major company will be impacted over the coming year. Changes on the horizon include:

- New tariffs and trade barriers driving up costs and forcing companies to rearrange their supply chains and also potentially sparking retaliation against U.S. businesses overseas, especially in China.

- Some countries restricting the flow of data across borders, increasing costs and potentially impeding the growth of data-driven global businesses.

- The growing number and stronger enforcement of financial crimes regulations that are increasing the cost and regulatory burden of doing business in some regions.

But there are also bright spots of global cooperation in the trade of goods, services, and data, as well as intellectual property protection. Businesses that can adapt to and engage in the evolving policy landscape will have the edge.

“This is a time of tremendous uncertainty for global companies, as the U.S. makes aggressive use of its trade tools,” says Ambassador Robert Holleyman, a former deputy U.S. trade representative, who is a partner at Crowell & Moring and president of Crowell & Moring International, the firm’s international policy and regulatory affairs consulting affiliate. “But it’s also a time of opportunity for companies that can engage in the necessary planning. Right now, you see more free trade agreements being negotiated by more countries, at a faster pace, than any time in history.”

|

"Right now, you see more free trade agreements being negotiated by more countries, at a faster pace, than any time in history." |

A Fractured Trade Picture

The world’s attention has been captured by the tough talk (and walk) of the world’s largest economy, as it revisits or revamps international trade deals, imposes tariffs on aluminum and steel and billions of dollars of Chinese imports, and reconsiders the proper role of the World Trade Organization in the America First era.

The Trump administration has also been granted greater authority by Congress to scrutinize or block foreign investments that might threaten U.S. control of key technologies. This move has enjoyed bipartisan support (see International Trade, page 12).

In North America, the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which could replace NAFTA, holds the promise of bringing trade relations within the continent somewhat back to normal. But the trade war with China appears unlikely to fully resolve soon, Holleyman predicts. The U.S. has been pushing China for fundamental market-oriented reforms—such as reductions in subsidies to state-owned enterprises and openness to foreign investment in sensitive technological sectors—that China has been in no hurry to implement, he notes.

Yet even as the U.S. has escalated its tariff war with China, “the rest of the world is moving more aggressively to strike new agreements that can reduce tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade,” Holleyman observes. He points to recent trade deals between the European Union and Japan and the EU and Canada; the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a 16-country inter-Asian negotiation; and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the agreement signed by 11 countries after the U.S. withdrew from its predecessor. The CPTPP went into effect in December 2018 and is now in force among seven nations.

As for the WTO, rumors of its imminent demise may be exaggerated, says Holleyman. The U.S. is unlikely to leave the WTO, and it (like the EU and Japan) continues to pursue WTO trade cases against China. The U.S. is also participating in planned WTO rule setting on digital trade and e-commerce.

With trade policy fracturing, the game of global commerce has grown in complexity—from checkers to chess. Companies must plan more intensively and think further ahead. “Every global company should be mapping out its supply chain—and its competitors’ as well—and analyzing them against various trade negotiations so that they can predict the impact of new agreements or tariffs,” Holleyman says. “You want to preserve your ability to do business but also find ways to expand your opportunities” (see sidebar, page 7).

|

"Even when companies are not the importer of record, U.S. customs is investigating whether (they) are conspiring or colluding with importers to circumvent those rules." |

Steering Through Trade Conflicts

In the absence of stabilized trade regimes, countries and companies will continue to use trade policy as a competitive weapon, says David Stepp, an International Trade Group partner with Crowell & Moring in Los Angeles. Stepp predicts a large increase in anti-dumping and countervailing duty cases as the Trump administration demonstrates its willingness to hear complaints by U.S. producers that they are victims of unfair competition. Even if these complaints are justified, a duty on a product meant to protect one group of U.S. manufacturers can send costs soaring for other domestic companies.

Stepp anticipates that the U.S. trade war with China will not be resolved quickly. The conflict has many companies weighing a variety of unpleasant options. “Moving all production outside of China can be an expensive and time-consuming process, especially for regulated industries where qualifying a new supplier can take a year or more. As a result, some companies will keep production in China and absorb as much of the added costs as possible,” Stepp predicts. This is especially likely in lower-margin industries like retail.

But some companies are finding ways to minimize the impact of tariffs. One strategy, known as tariff engineering, is to advocate with customs officials that an imported good is being listed under the wrong tariff classification and should be reclassified in a category not covered by a special duty. Conversely, other companies are arguing that a competitor’s imports are misclassified and should be covered by a special duty.

Other strategies include attempts by some companies to change the “country of origin” for their imported goods, for example by keeping some manufacturing in China but moving final production to a third country. If U.S. Customs rules that the product has been “substantially transformed” in this third country, then China might no longer qualify as the product’s country of origin and special tariffs would no longer apply.

Companies must tread carefully when attempting moves like these, Stepp says. “U.S. Customs is acting aggressively to enforce trade rules. Even when companies are not the importer of record, U.S. Customs is investigating whether companies are conspiring or colluding with importers to circumvent those rules,” he explains. General counsel should ensure that robust trade compliance programs are in place to handle the expected surge in enforcement actions.

As for the Chinese, they are retaliating against the new U.S. tariffs in multiple ways. Beyond increasing tariffs on U.S. exports, the government has the ability to make the business climate even more difficult for multinationals operating in China, by slow-walking licenses and permits, for example. “China is a highly regulated economy, so there are a lot of non-tariff ways to make life difficult for U.S. companies,” Stepp notes. For now, the Chinese government doesn’t want to discourage foreign investment, but it certainly can impose onerous measures if trade negotiations don’t go well with the United States.

What's in Your Supply Chain?

Trade conflicts could reduce opportunities for U.S. multinationals in countries other than China, Stepp says. “Other nations are retaliating against U.S. import tariffs with their own tariffs against U.S. exports. They’re also stepping up their own antidumping complaints and targeting U.S. exports such as agriculture that benefit from government subsidies,” he says.

As U.S. companies consider diversifying their sourcing to avoid current or potential tariffs, a good first step is to get a full understanding of tariff costs and of country-of-origin information from their major suppliers. Then they can look at opportunities to take advantage of reduced trade barriers under new trade deals that are signed or pending outside the United States.

Companies that have a better understanding of their supply chain are poised to reduce risks as well as costs. One example is in the area of consumer product safety. “All of this focus on tariffs is trickling into the consumer protection world because yet again companies are waking up to the fact they don’t always have complete visibility into their supply chain,” says Cheryl Falvey, a partner in Crowell & Moring’s Mass Tort, Product, and Consumer Litigation Group and the former general counsel of the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Supply chain transparency is key to compliance with consumer protection regulations in areas such as country-of-origin labeling and “Made in the USA” claims, Falvey says. Tariff scrutiny shines a bright light on where the product is assembled and from what parts. Today’s products can be assembled from a variety of components sourced from different locations all around the globe. “Traceability is also crucial if and when a component within a consumer product fails,” Falvey notes. “Manufacturers must be able to trace components to the factory and determine what went wrong if they are to limit the scope of any required corrective action or recall.”

|

"The focus on tariffs is trickling into the consumer protection world. ... Companies (see) they don't always have complete visibility into their supply chain." |

Falvey predicts technology enhancements will improve supply chain visibility and aid in compliance with regulatory requirements. “Blockchain has already received early adoption as a way to manage traceability in food supply, whether to demonstrate produce comes from a region unaffected by a foodborne pathogen or from a farm that meets standards for organic labeling. It has practical applications that will aid legal compliance in any product manufactured and shipped globally,” she says.

Analyze Your Supply Chain: 5 StepsWhile big free trade agreements like North America’s USMCA get much of the press, dozens of other agreements still under negotiation could also affect profits at global companies. “The vast majority of companies don’t have a coherent strategy for addressing these agreements,” says Ambassador Robert Holleyman, president of Crowell & Moring International and a former deputy U.S. trade representative. “They don’t have a clear grasp on how trade rules can affect their costs, or how advocacy can influence those rules.” The first step to making trade work for your company is to analyze how your supply chain is affected by existing or pending agreements. Here are five questions to ask when determining how a proposed agreement could affect your company:

|

Rethink China Strategy? Maybe Not

When analyzing whether to move production in response to trade conflicts, it’s important to take a holistic approach, says John Brew, a partner at Crowell & Moring and chair of the firm’s International Trade Group. China is a principal case. Rising tariffs and wages have many Western executives wondering whether it’s time to rethink their China strategy, and indeed, the per-unit cost of production there may be increasing.

Yet production shutdowns in China come with considerable costs, Brew says. Mass layoffs trigger notice and severance requirements. Equipment moves trigger duties. The time lost to moving and setting up new facilities elsewhere could lead to production delays. And then there’s the reputational cost of pulling up stakes. “Companies came in and built up these Chinese cities,” he adds. “If they pull out of China due to trade conflicts, will they be welcomed back when the trade winds change?”

The need to move could also be obviated by changing developments: The trade conflict could settle down, or wages in the new production country could increase. No one can predict the future, but a truly holistic spend analysis requires consulting with experts from throughout the company, including human resources, communications, tax, finance, and legal, Brew says.

|

"If companies pull out of China due to trade conflicts, will they be welcomed back when the trade winds change?" |

Where Does All the Data Go?

As with the case of goods and services, the outlook for the free flow of data across borders is decidedly mixed, says Frederik Van Remoortel, a partner in the Brussels office of Crowell & Moring. First the bad news: In countries such as Russia, China, India, and several African countries, data localization is on the rise. “The official reason is often the desire to protect the data of the individual and the security of the data in general, but behind the scenes, these rules are very often protectionist,” Van Remoortel says. “These governments want to ensure they can have access to the data and protect local providers.”

Data localization rules generally oblige companies to keep certain data—or a copy of certain data—inside the territory. Multinationals that would normally centralize their data or use cloud services must incur the higher costs and risks of storing, securing, and updating multiple copies. In countries such as China, the rules seem to go hand in hand with government censorship. U.S. tech industry groups are especially worried about China’s new cybersecurity laws, which have already resulted in Chinese authorities fining companies or ordering them to suspend operations.

Now the good news: More trade pacts and international agreements recognize the importance of cross-border data flows and include provisions to facilitate the free flow of (personal) data. Such provisions can be found in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement and the CPTPP, and the Asian-Pacific APEC countries have negotiated a cross-border privacy rule system to build trust in the cross-border transfer of personal information.

Similarly, in its recent trade agreement with Japan and in other negotiations, the EU is promoting free flow of personal data to countries with adequate data privacy rules. The European regulation on personal data, the GDPR, has been in effect since May 2018. “In 2019, global companies can expect GDPR enforcement to gather steam,” Van Remoortel says. EU member states will also implement the directive on security of network and information systems, which will, for instance, impose additional cybersecurity obligations on operators of essential services and key digital service providers.

Moreover, countries and states such as Brazil and California are weighing or implementing legislation that enshrines Europe’s GDPR data privacy principles. Global companies will hence be busy complying with a slew of new regulations relating to the protection of personal data and data flows in general.

|

Through data localization laws, certain "governments want to ensure they can have access to data and protect local providers." |

“Companies are taking data protection seriously; and many have someone at the board level responsible for it,” Van Remoortel notes. “We see many companies struggling with global implementation of data protection legislation.” It’s important to keep abreast of varying national regulations in areas such as data breach notification, Van Remoortel says. Given the likelihood of a data breach, companies must practice their response in many different jurisdictions well ahead of an actual occurrence. While all these laws impose their own regulatory burden, they also increase user confidence in data services, he notes.

“Many executives are still not aware of how data localization and data protection laws, in particular regarding data transfers, can impact M&A processes and related due diligence,” Van Remoortel adds. Obviously, potential acquirers should investigate whether targets are compliant in order to avoid buying risks. But the due diligence team itself may be breaking data laws if it transfers data out of the country for review.

Growing Protection for Intellectual Property

Intellectual property protection remains a big concern for global companies, and protection is still wanting in major markets such as China, India, Russia, Argentina, and Indonesia, according to recent reports by U.S. and EU authorities. Nonetheless, the long arc of history is bending toward stronger protection everywhere, says Teresa Stanek Rea, a partner at Crowell & Moring, a director with Crowell & Moring International, and former acting and deputy director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

“In general, IP is getting more respect, and protection is growing in sophistication, in each and every country,” Rea says. “In the U.S., there’s an ongoing controversy about whether the system is supporting patents and enforcement as much as it should be. Multinationals file patents and they want their inventions to be protected in all their markets. Most trade agreements recognize this, and the IP provisions in trade agreements try to provide consistency and predictability. But the rest of the world is getting strategic because they all want the innovation and industries that create jobs.”

|

"The rest of the world is getting strategic because they all want the innovation and industries that create jobs." |

Rea is heartened by patent modernization provisions in many of the new trade agreements discussed above and by recent national laws to protect trade secrets, a relatively new frontier in IP protection. She also points to the progress of the IP5, a working group of the world’s largest patent offices, in developing systems that make it easier for inventors to file for a patent in multiple offices.

When it comes to IP, the news media has fixated on the many tactics employed by China to strong-arm or even steal valuable knowledge from the U.S. and other nations. It’s unclear whether U.S. tariffs will compel China to fix this problem, but Rea says China is already improving IP protection as it seeks to protect its growing track record of domestic innovation. For example, some Chinese courts are showing more fairness to foreign companies in IP disputes.

Many executives don’t realize that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has IP attachés in U.S. embassies in 12 strategic locations around the world. Executives facing challenges in enforcing their IP rights can receive advice from their region’s attaché about how to proceed. The attaché also advocates with regional authorities for more favorable policies. “Businesses don’t always use the attaché to the extent they could,” Rea says.

“Multinational companies should think of their IP in the context of international trade,” Rea adds. “Multinationals should file patents and trademarks in every country in which they do business. They evaluate their IP to determine the strength of their proprietary position to determine likely market share.”

Financial Crimes Compliance Is Everyone's Problem Now

The Trump administration is poised to expand its aggressive use of sanctions, having commenced a new program against Nicaragua and expanded sanctions against Russia, Venezuela, and corrupt actors under its Global Magnitsky program, while re-imposing sanctions on old foe Iran. The so-called sectoral sanctions imposed on Russian and Venezuelan entities will be especially difficult for financial and nonfinancial companies alike because they allow some but not all transactions with designated entities, requiring U.S. persons to carefully consider transactions on an individual basis. The U.S. and the EU also have developed conflicting sanctions policies over Iran, complicating compliance decisions for companies that operate in both jurisdictions.

The low number of enforcement actions this past year was likely an anomaly; a rise is expected this year, says Carlton Greene, a partner at Crowell & Moring and a veteran of the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Greene expects in particular more enforcement of Russia sanctions, more enforcement against non-financial institutions, and more detailed guidance from OFAC on what it expects from U.S. companies with respect to the administration of their internal sanctions compliance programs.

Meanwhile, the enforcement and impact of anti-money laundering laws continue to grow. In the U.S., the nearly $600 million penalty against one bank shows that financial regulators continue to prioritize enforcement against AML programs they view as under-resourced, at a time when AML costs increasingly loom large in the operational budgets of banks and other financial institutions. A number of solutions to address this tension will continue to develop in 2019, including legislative proposals to alter reporting thresholds. New guidance from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and federal banking agencies appears intended to signal a favorable enforcement policy toward AML innovation. At the same time, Greene thinks that FinCEN and the FBAs have agreed to take a relatively forgiving approach to the biggest new piece of AML regulation banks are facing, FinCEN’s customer due diligence rule. But such forbearance will not last forever and will apply only where there are good faith efforts to comply.

In Europe, enforcement appears to be just getting started. Most recently, law enforcement raided the offices of a major international bank in connection with potential AML issues, not long after it was fined nearly $700 million for AML violations. In September 2018, Dutch bank Ing agreed to pay nearly $900 million in fines and disgorgement. And Danske Bank in Denmark now faces an estimated $630 million penalty for allowing Russian money to be laundered through it, with some reporting that the Department of Justice is also investigating. There has been talk of strengthening and centralizing EU AML regulatory authority in response. All of this is likely to lead to increased AML compliance expenditures for European institutions and the same pressure to seek innovative solutions that U.S. banks face, Greene believes.

Finally, Greene predicts that regulators in the U.S. are likely to make some progress in the coming year in efforts to negotiate their approach to the regulation of virtual currency and other digital assets. There are two key questions in this area: First, whether and when digital assets will be regulated as securities, and what will be the regulatory boundaries between FinCEN, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Second, nearly every U.S. state has its own money transmitter laws that may apply to such businesses. Greene sees a good likelihood for guidance from federal agencies on the first problem and for key regulatory approvals of new businesses that will help define a way forward for the exploding field of digital assets. The second issue is more complicated, but a growing number of states are working together to create reciprocal licensing arrangements. With regard to digital assets overall, the current path is toward tokenizing every conceivable form of asset, Greene says. This is complex, and “a large number of these businesses may fail,” he says. “But those that succeed are likely to change the world as we know it.”

The rising tide of sanctions, tariffs, rules, and barriers are complicating decisions for global companies. Companies that may be subject to this plethora of risks must read the winds carefully, tack as needed, and press on.

|

"A large number of [businesses based on digital assets] may fail. But those that succeed are likely to change the world as we know it." |

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26