Antitrust – Main Street vs. Wall Street: Plaintiffs' Bar Continues To Come After Large Banks

Publication | 01.09.18

[ARTICLE PDF]

Historically, Wall Street banks were rarely the focus of government antitrust investigations or private antitrust litigation. But that changed in the wake of the Great Recession. While most observers believed that antitrust scrutiny of the financial services sector was reaching its end, recent lawsuits filed by the private antitrust bar—which has secured hundreds of millions in settlements in the last few years—strongly suggest otherwise. It appears that banks will continue to have to defend themselves in costly antitrust litigation for the foreseeable future, regardless of whether the Trump administration makes antitrust enforcement in the financial services sector a priority.

Historically, Wall Street banks were rarely the focus of government antitrust investigations or private antitrust litigation. But that changed in the wake of the Great Recession. While most observers believed that antitrust scrutiny of the financial services sector was reaching its end, recent lawsuits filed by the private antitrust bar—which has secured hundreds of millions in settlements in the last few years—strongly suggest otherwise. It appears that banks will continue to have to defend themselves in costly antitrust litigation for the foreseeable future, regardless of whether the Trump administration makes antitrust enforcement in the financial services sector a priority.

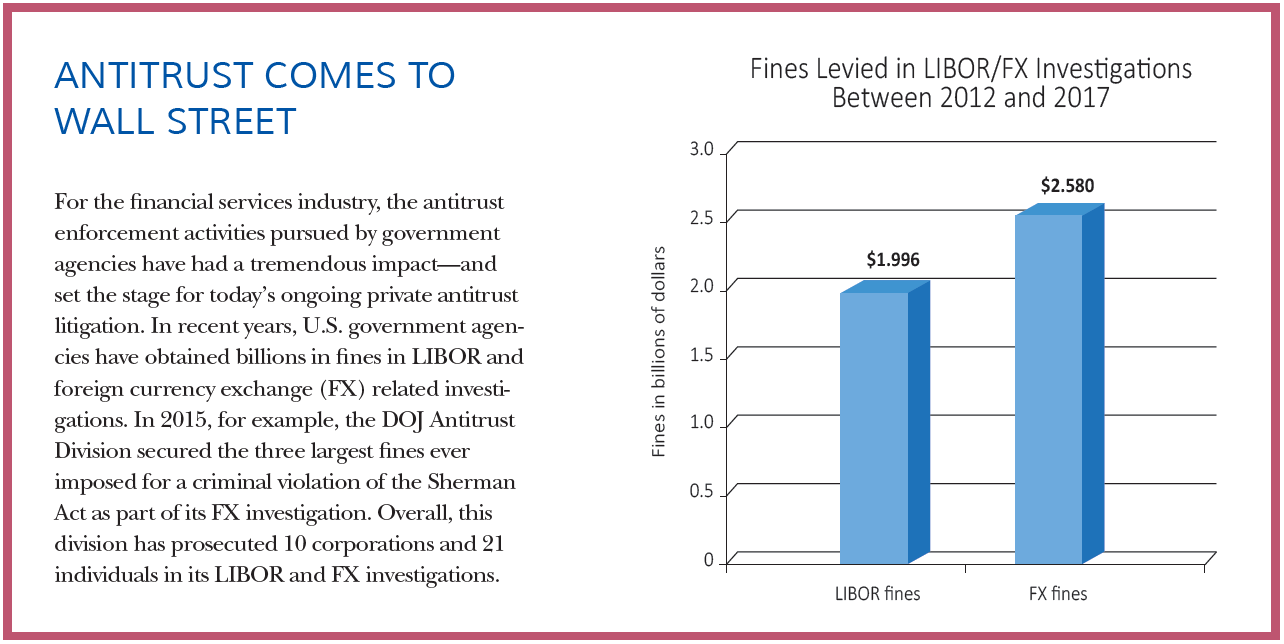

In the years following the 2008 economic crisis, government antitrust agencies in the U.S. and Europe ramped up their scrutiny of the financial services sector. In particular, there were lengthy investigations into whether a number of banks manipulated foreign exchange markets and the benchmark rates (such as LIBOR and EURIBOR) for various types of financial instruments. These investigations resulted in a number of large banks and their employees pleading guilty to criminal charges and agreeing to pay billions in fines.

As soon as these government investigations became public, the private antitrust bar filed a number of lawsuits alleging billions in damages. “Those and other government investigations resulted in a steady stream of private antitrust lawsuits alleging that banks unlawfully colluded to manipulate LIBOR and other benchmarks, fix the prices of various commodities, set ATM fees, and so forth,” says Juan Arteaga, a partner in Crowell & Moring’s Antitrust Group and a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

|

"Any hope that reduced government antitrust enforcement in the financial services sector under a Trump administration would result in less private litigation is being dampened by the filing of these recent lawsuits." |

By early 2017, however, many in the legal and financial services industries believed that the spike in antitrust litigation was starting to run its course. Cases were being settled and a new administration in Washington was signaling a pullback in regulatory enforcement. But that optimism now appears to be premature, and private antitrust litigation is still very much part of the landscape for the financial services sector—but with a new twist.

PLAINTIFFS’ BAR TAKES THE LEAD

A number of cases filed within the last year show that plaintiffs’ lawyers are no longer waiting for the announcement of a government investigation before filing antitrust lawsuits against banks. “They are starting to file on their own, thereby ensuring that litigation will continue even if there is less enforcement by federal antitrust authorities,” says Arteaga.

At the same time, plaintiffs are expanding their toolkit of legal theories. For years, private antitrust litigation focused largely on the alleged collusion among banks to manipulate various types of markets, as plaintiffs followed the lead of government enforcement efforts. More recent lawsuits, however, have shifted their focus to potentially anticompetitive conduct premised on group boycott and abuse of market power theories.

Arteaga cites a recent example in which six of the largest banks in the world formed a joint venture to facilitate the lending and borrowing of stock in support of short selling. In August 2017, several public pension funds sued those banks, alleging that they had collectively blocked other companies that had tried to enter this market with more efficient and lower-cost platforms and services.

“The complaint asserts that the banks illegally colluded with each other and agreed that they were going to boycott, as a group, these other companies in order to drive them out of business and protect the fees that they were getting from these transactions,” says Arteaga.

Large banks are dealing with other, similar cases. In June 2017, for example, a small trading exchange filed an antitrust suit that accused a dozen banks of conspiring to keep it out of the credit default swap market through a coordinated boycott of its trading platform. And, in a case currently working its way through the judicial system, investors are suing a number of large banks for allegedly working together to keep business away from three electronic exchanges set up to handle interest rate swaps.

Overall, says Arteaga, “any hope that reduced government antitrust enforcement in the financial services sector under a Trump administration would result in less private litigation is being dampened by the filing of these recent lawsuits. They indicate that antitrust litigation is going to continue to be a live issue for large banks. Looking ahead, banks need to think of this as their new normal.” In that environment, he adds, it is all the more important for financial institutions to implement robust antitrust compliance programs and consult with antitrust counsel before participating in any competitor collaborations.

To gauge the future level of litigation risk, banks can keep an eye on a number of private suits, including the financial benchmark litigations that began a while ago and may be resolved in the near future. “See how those play out,” Arteaga says. “If banks are still paying millions of dollars in settlements, that’s going to incentivize the private plaintiffs’ bar to continue to go after these institutions in new and creative ways.”

EMPLOYERS BEWARE: CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE EMPLOYMENT PRACTICESIn recent years, the hiring practices of large corporations have come under attack from federal antitrust agencies and the plaintiffs’ bar. DOJ’s Antitrust Division, for example, brought a series of cases against a number of tech giants for entering into “no-poach” agreements whereby they agreed not to hire each other’s employees. “Plaintiffs’ lawyers filed follow-on actions that settled for close to a billion dollars, and they have recently challenged the HR practices of several Fortune 500 companies,” says Crowell & Moring’s Juan Arteaga. Last October, the stakes increased considerably when DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission issued new guidance regarding employment practices. “This guidance upped the ante by announcing that companies and employees that engage in naked wage-fixing or no- poaching agreements will be prosecuted criminally,” says Arteaga. “That means that companies and employees that engage in these practices could be forced to pay significant fines and spend time in jail. It also means that plaintiffs’ lawyers have another potentially powerful tool to use in litigation.” In a recent speech, a senior DOJ official signaled plans to enforce these guidelines, saying the business community “should be on notice” that wage-fixing and no-poach agreements will be prosecuted criminally. Consequently, companies should institute the appropriate safeguards, including training HR and other employees who participate in hiring and compensation decisions, says Arteaga. |

PDF Download

Web Flip Book

Click to access the flipbook.

- "Data, Data Everywhere – Positioning Your Company to Survive and Thrive in the Data Revolution." — Cheryl Falvey, Paul Rosen, Cari Stinebower, Ryan Tisch, and Kent Goss.

- "Antitrust – Main Street vs. Wall Street: Plaintiffs' Bar Continues To Come After Large Banks." — Juan Arteaga.

- "Environmental – Regulatory Rollback—And Pushback." — Kirsten Nathanson.

- "Government Contracts – Contractors: Getting Their Due." — Stephen McBrady.

- "Jurisdictional Analysis – Time to Trial, Favorable Courts & Other Litigation Trends." — Keith Harrison.

- "Intellectual Property – TC Heartland Reshapes the Patent Litigation Landscape." — Jim Stronski.

- "Labor and Employment – Pay Equity: The Shifting Landscape." — Trina Fairley Barlow.

- "Torts/Products – The New State Lottery: Litigation Rather Than Regulation." — Rick Wallace.

- "White Collar – Corporate Monitors: Peace, at What Cost?" — Philip Inglima.

- "E-Discovery – What is 'Proportional' in the Era of Expanding Data?" — Mike Lieberman.

- "Arbitration – Unlocking the Promise of Arbitration." — Aryeh Portnoy.

- "Health Care – FCA Enforcement: Different, But Still Here." — Laura Cordova.

- "IP: Copyright – 3D Printing Complicates Copyright." — Valerie Goo.

- "Tax – What Congress Giveth, the IRS Taketh Away." — Dwight Mersereau.

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26