Antitrust - Agencies Show New Willingness to Litigate

Publication | 01.19.16

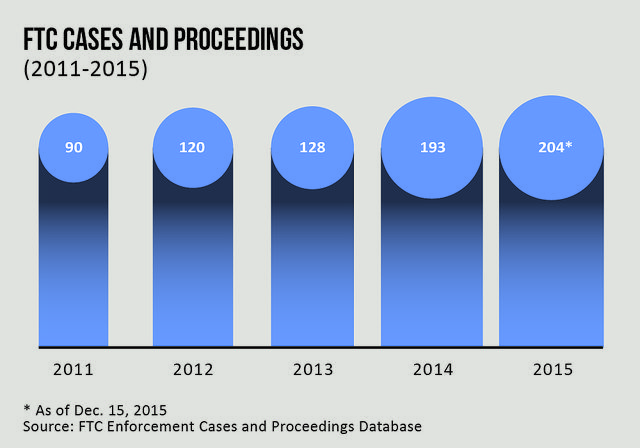

Antitrust agencies are bringing more cases — and exacting big penalties.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) do not always win in antitrust litigation, and the government, of course, has the burden of proof—but that has not stopped them from going to court. "The agencies have been trying more cases—and they're increasingly winning a lot of them," says Jason Murray, a partner in Crowell & Moring's Antitrust Group. "It's happening across industries—no sector is immune."

For example, last year, the DOJ filed suit to prevent Electrolux's $3.3 billion purchase of GE's appliance division, and sued four Michigan hospitals over their agreement not to advertise in each other's territories. In February 2015, the DOJ won a trial in district court after claiming that American Express's rules limiting merchants' promotion of other credit cards were anticompetitive. In September 2015, KYB Corp. agreed to plead guilty and pay a $62 million criminal fine for its role in a price-fixing conspiracy involving shock absorbers that were installed in numerous vehicles sold in the United States.

The FTC has also been increasingly active in court. In June 2015, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia granted an FTC request for a preliminary injunction blocking the proposed merger of Sysco and US Foods, prompting the companies to abandon the deal. Shortly before that, the Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld an FTC ruling that McWane, a supplier of iron pipe fittings, had maintained a monopoly by excluding competitors. FTC litigation even found its way to the Supreme Court: In FTC v. North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners, the court ruled that the licensing board—which had been warning non-dentists to stop offering teeth-whitening services—was not protected by state action immunity and was therefore subject to FTC antitrust oversight.

"The fact is that the odds of actually going to court in an antitrust matter are higher than they have been in recent memory," says Murray. "When you're involved in merger reviews or investigations, you always evaluate whether you want to settle, but you need to be prepared to put them to the test in litigation. The agencies are clearly ready to litigate."

The government also is more willing to use disgorgement as a penalty for antitrust violations. Disgorgement has traditionally been an uncommon remedy in antitrust cases, but more recently it has come up in several cases. In early 2015, for example, the DOJ settled a suit with two New York City tour bus operators and their Twin America joint venture for $7.5 million, based on the gains made through anticompetitive behavior that led to price increases for consumers.

The FTC has also made significant use of disgorgement over the past year. Most notably, it reached a $1.2 billion disgorgement settlement with drug maker Cephalon for entering into a "reverse-payment" agreement in which Cephalon paid generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of a generic version of Cephalon's sleep-disorder treatment. The use of disgorgement represents a change in tactics for the FTC that many observers find troubling—including some at the FTC itself. In a statement on the Cephalon case, two FTC commissioners, referring to disgorgement, expressed "continuing concerns about the lack of guidance the commission has provided on the pursuit of this extraordinary remedy in competition cases."

"We're seeing that the agencies are not only more willing to go to court over antitrust issues, they're also willing to use a wider variety of tools from their litigation tool box—even controversial ones—in order to provide what they believe is relief for consumers," says Murray. That risk of litigation is not going to diminish anytime soon, he says. "Some FTC commissioners, and the chief economist at the FTC, have explained that they see the increased emphasis on litigation as an effective response to what they believe are a growing number of obstacles to consumer class action antitrust suits."

ROBINSON-PATMAN RETURNS

Disgorgement may not be the only area where seldom-used antitrust enforcement tactics are returning to the stage. In Woodman's Food Market, Inc. v. The Clorox Co., Woodman's sued Clorox for violating the Robinson-Patman Act. Due to a change in its distribution model, Clorox had stopped selling bulk-size packages to Woodman's, while continuing to sell them to national stores such as Costco. Woodman's claimed that this was price discrimination based on package size, under sections 2(d) and 2(e) of the act. The Wisconsin Federal District Court refused to dismiss the case, and the issue was immediately appealed to the Seventh Circuit.

"There really hasn't been much litigation under Robinson-Patman for the last 10 years or more," says Murray. Moreover, he says, "this is the first time that a federal court has weighed in on this type of claim, and it could end up being one of the few times that the courts have expanded the scope of the act." If Woodman's wins, he adds, it could prompt more private litigation under Robinson-Patman.

[The FTC has been focusing on anticompetitive activity in recent years, which has led to a growing number of enforcement actions against companies.]

The Ongoing Evolution of Pay-for-Delay

The U.S. Supreme Court's Actavis "pay-for-delay" ruling continues to play out, as state and federal courts try to understand and apply the Court's framework. For example, in the May 2015 Cipro ruling, the California Supreme Court said that pharmaceutical companies' pay-for-delay agreements can be considered unreasonable restraints of trade under state law. In addition, it laid out a structured rule-of-reason test with several clear steps for assessing when pay-for-delay settlements are anticompetitive. "It's a fairly detailed set of factors, and it addresses an area that Actavis had not addressed," says Murray. The Cipro ruling is likely to make it harder to defend pay-for-delay cases in California. In time, other state and federal courts may end up drawing on the California test as well because the structured rule-of-reason assessment provides a defined approach that can be easily replicated by other courts seeking to apply the Actavis framework.

Meanwhile, a Third Circuit appeals court ruling looked at the question of non-cash compensation in pay-for-delay agreements—another area left open by Actavis. That case—In re Lamictal Direct Purchaser Antitrust Litigation—involved an agreement in which Glaxo agreed to allow Teva to sell generic forms of Glaxo's Lamictal product before the patent had expired, and Glaxo agreed not to sell its own generic version of Lamictal. The appeals court said in June 2015 that Actavis does apply to such non-cash settlements, explaining that the agreement could be seen as an "unusual, unexplained reverse transfer of considerable value from the patentee to the alleged infringer," raising the possibility that it was "a payment to eliminate the risk of competition."

Together, says Murray, "these two rulings can be expected to encourage plaintiffs' firms to pursue more of these pay-for-delay cases in both state and federal courts."

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26