Supreme Court Forecast

Publication | 01.19.16

Is a Judicial Check on Administrative Authority Coming?

Last year was a year of blockbuster Supreme Court decisions, with the justices resolving high-profile, hotly contested disputes on the issues of same-sex marriage, health care, environmental law, and more. But Court watchers say some of these decisions might have also set the stage for a 2016 showdown on a question with profound implications for every industry subject to federal regulation: how much power should federal agencies have absent clear congressional direction?

For several decades, the courts have given considerable leeway to federal agencies when they interpret statutes passed by Congress as well as when they interpret their own regulations. In its 1984 ruling in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, the Supreme Court set the standard: if an agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute is reasonable, then it is to be given “controlling weight.” The 1997 case Auer v. Robbins recognized that even more deference is to be given to agencies’ interpretation of their own regulations.

But in recent Court opinions, the Court’s four conservative justices have signaled increasing discomfort with the latitude currently afforded to the executive branch. “Eventually, this issue will come to a head,” says Cliff Elgarten, a Crowell & Moring Litigation Group partner and a former Supreme Court clerk. “This may be the term when that happens.”

In the 2015 case Michigan v. EPA, the 5-4 majority found the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) interpretation of section 112 of the Clean Air Act to be unreasonable because EPA did not consider the cost of compliance before deciding whether to regulate hazardous air pollutants from power plants. In doing so, it applied Chevron deference, but signaled a narrower view of what is considered “reasonable.” As Dan Wolff, chair of Crowell & Moring’s Administrative Law & Regulatory Practice and a member of the firm’s Litigation and Environment & Natural Resources groups, explains, “If the language is ambiguous, then there are at least two potential interpretations. On the one hand, it has been true since our founding that the courts decide what the law means. On the other hand, there is the notion that agencies charged by Congress with administering regulatory programs should be given discretion to fill in the gaps left open by Congress.”

Writing the majority opinion in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) challenge King v. Burwell, Chief Justice John Roberts suggested that Chevron might not apply in cases of profound “economic and political significance,” appearing, in essence, to carve out a new exception to the deference doctrine.

A challenge to the EPA’s Clean Power Plan could provide the next test of administrative deference standards, says Tom Lorenzen, a member of Crowell & Moring’s Environment & Natural Resources, Appellate, and Government Affairs Groups. Relying on the authority the EPA says it has under the federal Clean Air Act (CAA), the agency in August 2015 unveiled sweeping state-by-state limits on CO2 emissions from existing power plants. “This rule affects vast segments of the American economy, so it fits in the King v. Burwell mold when it comes to deference,” says Lorenzen, who was an assistant chief of the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division from 2004 to 2013. “It seems this is the one to watch.”

Some observers believe challenges to the FCC’s controversial net neutrality order—which imposes open Internet requirements on broadband access providers—could also present administrative deference issues. But Elgarten points out that Chevron and Auer issues arise in a wide variety of regulatory contexts. “It is difficult to predict where and when the Court will choose next to grapple with these issues,” he says.

NO TRICKLE DOWN—SO FAR

Elgarten adds that, so far, conservative Supreme Court skepticism of deference toward administrative agency interpretation has not trickled down to lower federal courts. Even in the wake of the King v. Burwell decision, Wolff notes, in most cases the lower courts are probably not going to veer from the traditional Chevron and Auer tests absent further guidance from the Court. “That said,” Wolff adds, “a rulemaking such as the Clean Power Plan is of such significance that it could well embolden the D.C. Circuit to say, ‘This is an issue of such national importance that we’re going to decide what’s the proper interpretation.’ But that would be the outlier, at least for now.”

Lorenzen adds that he doesn’t see executive branch agencies becoming any less assertive about applying their own interpretations of statutes or regulations. “With Congress unwilling or unable to act on many big issues, that leaves the law somewhat frozen, and the administration is attempting to grapple with new problems based on old laws,” he says. And in fact, in Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Association, decided this past term, the unanimous Court clarified that when an administration interprets an existing regulation in a new way, it need not do so through notice-and-comment rulemaking.

Be that as it may, Wolff notes, a trio of concurring opinions in Perez cautions agencies not to run too wild with new interpretations, lest they push the conservatives to reconsider deference under Auer. Lorenzen agrees, noting that if the Obama administration uses its final year to continue cementing its legacy through administrative action, as expected, the agencies may be more deliberate in the way they present interpretations in light of the recent Supreme Court skepticism, in anticipation of additional court challenges. Lorenzen points out that the Supreme Court’s liberal wing has expressed no reservations about the broad application of administrative deference, seeing the concept as “viable and robust.” Because the next court vacancy is expected to come from the liberal side of the court, he notes that the 2016 presidential election could be a deciding factor in the future of administrative deference. “The next appointment to the Supreme Court is going to be very significant,” he says. “Whether that appointment is made by a Democratic president or by a Republican president will make a very big difference on this and many other issues.”

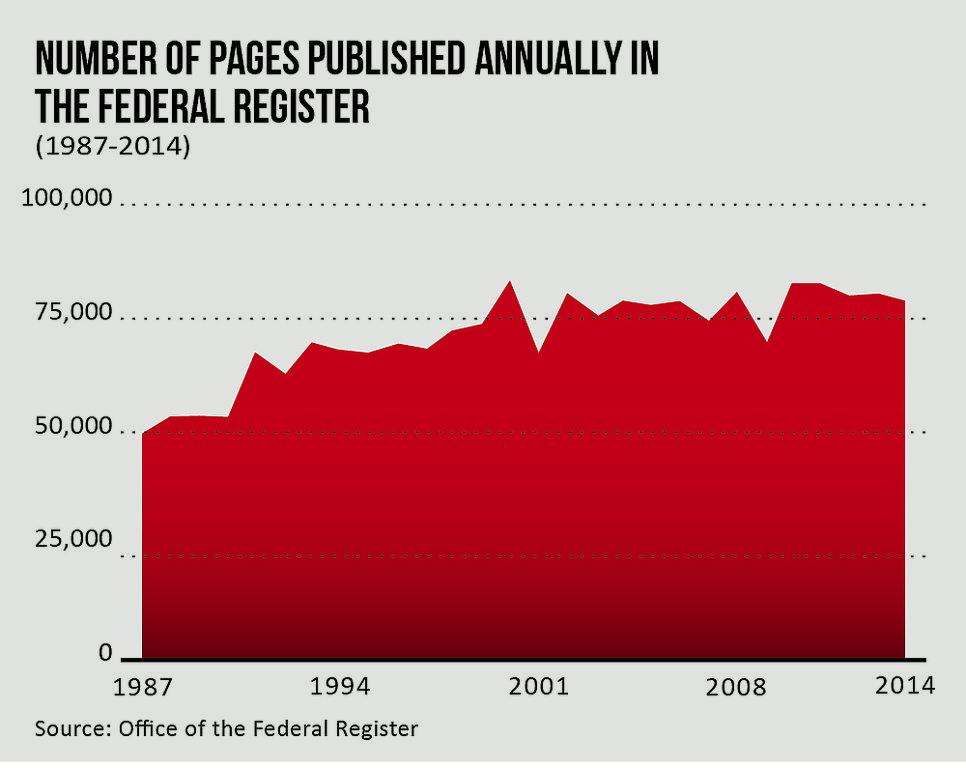

[There has been a steady increase in the number of pages published each year in the Federal Register, which includes public notices, proposed rules, and final rules issued by federal administrative agencies. Some conservative Supreme Court justices have been questioning the broad latitude given to federal administrators in creating and applying these rules.]

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Regulatory

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26