Class Actions - Battling on the Front End of Litigation

Publication | 01.19.16

Today, a great deal of litigation is testing the validity of important defense tactics in class actions—and possibly reshaping courtroom strategies.

Over the past few years, many class action defendants have attempted to moot—or "pick off"—plaintiffs by offering to pay the maximum amount the plaintiff could recover. Whether the plaintiff accepts or not, the offer moots the individual claims and the class action—or so the theory goes. "One argument is that under the scheme of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 68, the claims are mooted if the plaintiff fails to accept an offer of full relief. The other, more fundamental argument is that the plaintiff no longer has standing under Article III of the Constitution to pursue the case," says Steven Allison, a partner in Crowell & Moring's Class Actions Group.

In cases where damages are set by law, the calculation of such offers is fairly straightforward. "If a plaintiff is offered enough to cover that maximum amount, they no longer have standing, because they have been offered everything that they're entitled to and they are not harmed," says Allison. "The plaintiff then arguably cannot serve as a class representative."

While companies that have to defend themselves in class actions find this argument appealing, not all courts see it that way. The Ninth and Eleventh Circuit Courts have ruled that such offers do not moot the class action claim. The Third, Fourth, and Sixth have said that they do. So too had the Seventh Circuit—but it reversed itself in Chapman v. First Index in August 2015, when it ruled that an unaccepted offer of judgment does not moot a class claim.

The issue has reached the U.S. Supreme Court in Campbell-Ewald Co. v. Gomez. In this case, the plaintiff received an unsolicited recruiting text message from Campbell-Ewald, a marketing company doing work for the U.S. Navy, and filed a putative class action under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act. The company offered a settlement of $1,500 (the maximum damages under the act) plus costs, but the plaintiff did not accept the offer. The trial court ruled in favor of the company, but the Ninth Circuit then reversed the decision, saying that an unaccepted settlement offer does not moot the class action claim.

"If the mooting of class plaintiffs is validated by the Supreme Court, it becomes a very powerful defense tool," says Allison. If not, this tool will not be available, although other uses of unaccepted Rule 68 offers, such as attacking the adequacy of the class representative, may still be available. Even if the Supreme Court does validate the practice, he says, "there will still be a lot of secondary litigation about whether an offer is full relief or not. In a lot of statutes that set damages, it's not clear what to do about attorneys' fees, for example. So you get into questions of how much someone was really harmed, and it can get tricky."

WHO'S IN, WHO'S OUT?

One of the most basic questions in a class action is who is in the class. And courts continue to struggle with the methods used to answer that question.

"The issue of ascertainability comes up a lot, especially in food and false advertising cases," says Allison. "If you're talking about a case involving a lot of low-price products, like cereal, people don't keep records of their purchases. So how can you know who legitimately belongs in the class?" One approach is to essentially have class members identify themselves through affidavits—and some courts have rejected that approach, while others have approved it.

The current focus on ascertainability has been driven in part by the Third Circuit's Carrera v. Bayer Corp. decision, which said that methods for determining ascertainability could not require "individualized fact-finding or mini-trials," as with signed affidavits, and needed to be "reliable and administratively feasible" and allow defendants their due process right to challenge class membership. Since then, says Allison, "there have been numerous challenges to the ascertainability of classes. And there has been a significant split among the various circuit courts on the issue." For example, recently in Mullins v. Direct Digital, LLC, the Seventh Circuit rejected the "heightened ascertainability" standard of Carrera.

Jones v. ConAgra Foods, Inc., a high-profile ascertainability case on appeal in the Ninth Circuit, bears watching, especially given the volume of false advertising and food-related litigation in that circuit. Here, the plaintiffs claimed that ConAgra used a variety of misleading labels for different canned tomato products over a six-year period, and suggested having class members identify themselves through sworn statements. The District Court rejected that approach, saying that people could not be expected to accurately recall all the ConAgra products they had purchased over the years and then remember which ones had which labels.

The Ninth Circuit's ruling in Jones will shed more light on ascertainability challenges, especially in a key jurisdiction. "But it would be one more indicator, not the final answer," says Allison. And if a split continues between key circuits, he says, "it's going to start a real battle to be in a favorable jurisdiction, and perhaps lead to something that the Supreme Court will decide to take up."

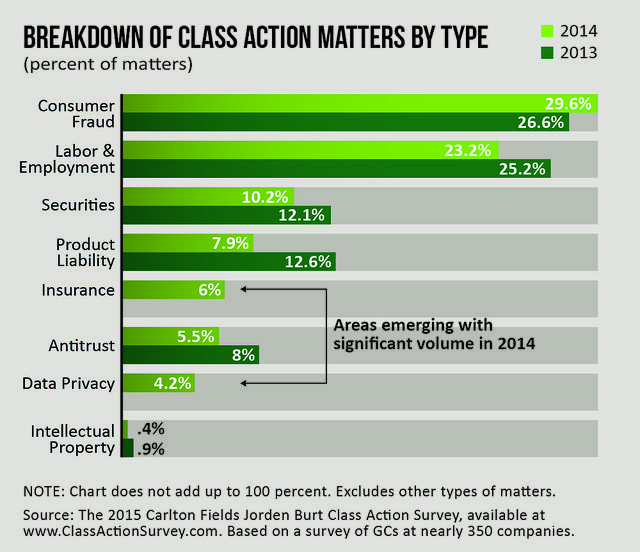

[Consumer fraud and labor and employment still account for the lion's share of class action lawsuits, but courts are seeing a growing number of insurance and data privacy class actions.]

TCPA Exposure Increases

For years, the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA), which prohibits companies from making unsolicited electronic contact with consumers, has been a key driver of class actions. And with recently revised FCC regulations, the act is likely to be the source of even more litigation.

In a July 2015 order, the FCC broadened TCPA liability for companies that contact consumers via phone, text, or fax. It also left a number of terms undefined and created gray areas that may make compliance difficult, says Allison. "The FCC order has made these TCPA class actions more likely, and more difficult to defend," he says. "Virtually every business that has any kind of affirmative phone or text outreach to customers will see increased exposure to TCPA class actions." For those companies, he says, "you absolutely have to have a robust TCPA compliance program in place, as you are a likely target."

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26