Antitrust in the Digital Age

Publication | 02.26.20

[Article PDF]

Something was different at the ABA Antitrust Section’s Spring Meeting last year, where hundreds of the nation’s leading antitrust lawyers gathered amid the white marble and 55-foot custom sculpture of the Marriott Marquis in Washington, D.C. Among the usual discussions, government officials confirmed their heightened interest in technology firms and attendees buzzed about the greatest question to face the global antitrust community in decades: What were regulators planning for “Big Tech”?

Two months later, the House Judiciary Committee announced it would launch an investigation into the leading tech companies. Inquiries by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission followed, as did a Senate hearing. By fall, every state attorney general had joined a probe of at least one major Big Tech platform.

“The antitrust world hasn’t seen an issue this large in decades. Unlike every major antitrust development of the past, a look into Big Tech involves companies that may not charge customers anything and whose assets involve private consumer data that may not be able to be transferred as part of a remedy,” says Shawn Johnson, a partner at Crowell & Moring and co-chair of its Antitrust Group in Washington, D.C. “And this is not just about Big Tech. In the end, all companies are becoming digital. From how we view the role of data privacy to so-called killer acquisitions, these investigations are going to impact a wide range of businesses for years to come.”

|

"From how we view the role of data privacy to killer acquisitions, these investigations will impact a wide range of businesses for years to come." |

While an imminent breakup of any Big Tech firm is unlikely, the increased attention to antitrust issues has implications far beyond the handful of companies that dominate the news. These new developments could affect mergers, acquisitions, and business practices in virtually every sector. That’s because competitive advantage today is often reliant upon access to key data, to online platforms, and to cutting-edge technologies—and antitrust legal and regulatory action sets the rules for such access.

“This is a megatrend,” says Wm. Randolph Smith, a partner at Crowell & Moring in Washington, D.C., former chair of the firm’s Antitrust Group, and a former executive assistant to the chairman of the FTC. “A confluence of events, including political philosophy, economic impact, and missteps on issues like privacy, is creating a shift in antitrust focus and thinking that could reverberate into other sectors.”

|

"A confluence of events is creating a shift in antitrust thinking that could reverberate into other sectors." |

So Big. So What?

Big Tech platforms stand accused of a multitude of sins: invasion of privacy; lax data security; unfair treatment of labor, content, or merchandise suppliers; bias against competitors; failing to vet dangerous products or content; and the acquisition of incipient competitors in an effort to squelch future competition, a phenomenon some have labeled killer acquisitions.

Many of these platforms have prospered because they provide a superior service at a lower cost, or for free. But they also have benefited from the “network effects” that tend to favor technology incumbents. Along the way they’ve collected vast quantities of data about customers or users that critics contend entrench their dominance. “Antitrust enforcers are struggling to figure out how to define and police the amount of market power these platforms have amassed, particularly with respect to the collection and use of personal data,” says Jeane Thomas, a Washington, D.C.-based partner in Crowell & Moring’s Antitrust and Privacy & Cybersecurity groups.

|

"Antitrust enforcers are struggling to figure out how to define and police the amount of market power these platforms have amassed." |

Within antitrust circles, a debate has emerged about whether current law and legal precedent suffice to address the alleged challenges presented by Big Tech platforms. For nearly 40 years, antitrust law has been dominated by the idea that consumer welfare is the ultimate goal of antitrust enforcement. Some critics have vigorously challenged that standard, especially when it comes to mergers and dominant-firm conduct, and blame what they view as weak antitrust enforcement for increased market concentration and market power. Others have sought to defend the standard, while still others are actively seeking to define a new middle ground that is at once economically grounded yet acknowledges that increased antitrust enforcement is warranted, notes Crowell & Moring senior counsel Andrew Gavil, a former director of the FTC’s Office of Policy Planning and a member of the firm’s Antitrust Group in Washington, D.C.

Yet the source of Big Tech’s alleged dominance may lie less in legal doctrine than in missed opportunities for more aggressive antitrust enforcement. Many important acquisitions by Big Tech companies in recent years have flown under the radar from an antitrust perspective, notes Johnson. Antitrust enforcers haven’t challenged these deals, likely because the acquired company was viewed as operating in an adjacent or differentiated space. But with the benefit of hindsight, it is likely that some of these companies would have developed into potential competitors, such that a killer acquisition had occurred. “The platforms are thinking 10 years ahead,” Johnson says.

“The current wave of concern about Big Tech mirrors previous eras when antitrust was in the spotlight, such as when supermarkets and shopping malls were hurting Main Streets across America,” says Smith. Beyond acquisitions, big company behavior can raise competitive concerns when the companies take measures to hold onto the power they already have. Or as Smith puts it, “It’s often not what you do to become king of the hill, it’s what you do to stay there” that attracts antitrust attention.

It’s far from clear, however, whether antitrust enforcement is the answer to the problems ascribed to Big Tech. A prime example is concern about the protection of privacy. “Traditionally, privacy concerns have played virtually no role in antitrust enforcement,” says Thomas. “But the platforms have grown so large that some users want, and to some extent need, to be on these platforms so much so that they feel forced to give up significant privacy in exchange.” Some markets might benefit from competitors that would do a better job protecting privacy.

“Privacy protection and competition protection are on a collision course,” Thomas says. If platforms are leveraging customer data to foreclose competition, a typical antitrust solution would be to require them to make that data available to competitors. But this might mean the sharing of personal data, which would be unacceptable to most people. One prominent platform has already withheld information from advertisers about how viewers are interacting with their ads— creating anticompetitive concerns—by saying it must conform with European and California privacy laws. “Regulators are going to have to make some policy choices to say whether or not we’re willing to trade off harm to competition to protect personal data,” Thomas says. “In any case, privacy protection may be better addressed through consumer protection laws, for example by forbidding platforms from collecting certain information or from using it in certain ways.”

Feds Crack Down on Procurement CollusionAbout 40 percent of all federal discretionary spending goes to contracts for goods and services. Much of that goes to industries that are consolidating. That consolidation increases the potential for anticompetitive coordination during the bids and proposal process. Last November, the Department of Justice announced a Procurement Collusion Strike Force, an interagency partnership of the DOJ’s Antitrust Division, U.S. attorneys, the FBI, and various inspectors general that will conduct joint investigations, train government procurement officials to identify collusion, and educate government contractors on criminal antitrust law. It will also seek to “improve data analytics to identify red flags of collusion in government procurement data.” Tech firms are already heavily involved in government contracting, and the participation of Big Tech firms in government contracting continues to increase. Under the DOJ’s own criteria, the conditions in which Big Tech operates are favorable for potential collusion: relatively few sellers control a large fraction of the market; they often work together; and they often exchange employees, says Gail Zirkelbach, a Los Angeles-based partner in Crowell & Moring’s Government Contracts and Investigations groups. As previous interagency efforts have netted charges and convictions, this crackdown should be taken seriously, says Zirkelbach, a member of the firm’s Procurement Strike Force Strike Team, a multidisciplinary team that assists clients reacting and responding to the new strike force. The team recommends that companies, including high tech, review their training and compliance programs to ensure they are sufficiently robust. “If employees’ behavior gets the DOJ’s attention, the company could end up suffering the cost, disruption, and potential reputational harm of an lengthy investigation—even if it turns out that no violation occurred,” she cautions. |

Guidelines Ahead

With so many investigations underway, it might seem to some that the era of Big Tech is coming to an end. In reality, experts say, the course of change in 2020 is likely to be slow and incremental—though a change in the political balance of power in Washington could open the door to new legislation that would upend existing judicial precedent.

In January, the DOJ and the FTC jointly released new draft guidelines governing vertical mergers. The FTC has also said that it is developing additional digital platform enforcement guidelines as well as an addendum to 2006 horizontal merger guidelines that would address nascent competition and how the agency analyzes non-price effects of mergers. “Agency guidelines are significant for many reasons,” says Alexis Gilman, an antitrust partner at Crowell & Moring in Washington, D.C., and former head of the Mergers IV Division at the FTC. “They’re a useful road map of the agencies’ own analyses, which make them an important cue for companies that want to understand how the agencies might react to proposed deals. But they also influence how courts analyze issues, especially given the relative paucity of case law.”

|

"Agency guidelines also influence how courts analyze issues, given the relative paucity of case law." |

The draft vertical merger guidelines, however, were less aggressive than many observers had expected. “I don’t see them having a significant impact on vertical merger enforcement,” says Johnson. “They don’t reflect a fundamental shift in law and enforcement policy.” The two Democrats on the FTC abstained on the guidelines, arguing they were too soft. The guidelines identify effects that agencies will evaluate in determining whether to challenge a transaction, such as raising rivals’ costs. They also identify a market-share threshold below which agencies are unlikely to challenge a merger.

The efficiencies arising from vertical mergers will continue to make agencies reluctant to formally challenge transactions unless they raise serious competitive concerns, Johnson says. Yet the mere fact that the guidelines were revised reflects closer scrutiny of deals by both state and federal regulators in many areas besides tech. That includes health care, where the quest for “integrated care” has inspired a significant number of vertical acquisitions. Last June, for example, the FTC announced a settlement between two major health care companies that required the acquirer to divest certain regional operations. The deal also led to a settlement with the Colorado attorney general. Importantly, the changes to the vertical merger guidelines will affect every industry in which companies seek to create efficiencies through vertical integration—not just health care or Big Tech.

Rise of the Enforcers

In remarks to a group of state attorneys general last December, the U.S. attorney general noted the rare bipartisan support for closer scrutiny of digital markets. The FTC and the DOJ have each launched new efforts focused on technology. In March 2019, the FTC announced the formation of its Technology Task Force, which has since become the full-fledged Technology Enforcement Division. TED will review conduct and mergers in any market “where digital technology is an important dimension of competition,” according to the agency. Areas of focus may include killer acquisitions, “self-preferencing” by platforms, and exclusionary data practices. “The division is well staffed and its ambit is broad, so its investigations are likely to be thorough, wide-ranging, and lengthy,” says Gilman. The DOJ announced its own review into leading online platforms in July 2019.

It’s highly likely that these agencies will initiate enforcement actions this year, says Gavil. However, “they will be more targeted than people think, given the public debate,” he says. Rather than pursuing full breakups, agencies will focus on mergers or particular conduct alleged to be anticompetitive. In many cases, the actions will result in consent decrees in which companies agree to measures including targeted divestitures, elimination of anticompetitive contractual provisions, or less severe design changes.

“The investigations will likely create a flood of follow-on litigation by private companies and individuals who claim to be harmed by anticompetitive practices,” says Jason Murray, a Los Angeles-based litigator and co-chair of Crowell & Moring’s Antitrust Group. “Competitors, suppliers, vendors, and customers could attempt to recover damages in private lawsuits based on theories established or prosecuted by the government.” State attorneys general could sue on behalf of excluded competitors; individual customers, or “indirect purchasers,” could join massive, multidistrict class action suits. “These suits will multiply and drag on for a decade,” Murray predicts.

|

"The investigations will likely create a flood of follow-on litigation by private companies and individuals who claim to be harmed by anticompetitive practices." |

But any litigants that choose to pursue an antitrust remedy in the courts—whether agencies, states, or private entities—will run into legal doctrines that have set a very high bar for plaintiffs, particularly standards relating to exclusion and the duty to deal with rivals, says Lisa Kimmel, a senior counsel in Crowell & Moring’s Antitrust Group in Washington, D.C., who formerly served as FTC attorney advisor on antitrust and competition policy matters for then-chairwoman Edith Ramirez. “The case law has been very defense-friendly for many years, especially for monopolization cases. Novel theories are unlikely to prevail under the existing state of antitrust law, which means there may be a disconnect between what U.S. enforcers want to do and what they can actually get done absent legislation that alters the status quo in the courts.”

|

"There may be a disconnect between what enforcers want to do and can get done absent legislation that alters the status quo." |

With the courts and long-standing precedent acting as a backstop, a sea change in antitrust will likely require new laws from Congress. And substantive new laws are unlikely unless a bipartisan consensus coalesces around specific reforms or this year’s election results in single-party control of Congress and the White House, Gavil believes.

Ripple Effects

Regardless of whether this new wave of antitrust investigations results in a major change in law or legal doctrine, it could still have a significant effect on business well beyond Big Tech. That’s because it could impact the robust markets for data and disruptive technology that drive the economy in this era of digital transformation.

“The mere fact of the investigations is already affecting the market,” Gavil says. “It influences investors, venture capitalists, and innovators.” Potential competitors to the Big Tech platforms have been emboldened, the big platforms are more cautious, and some innovators who were looking forward to having their companies bought “could be disappointed.” The likely sources and shape of innovation may well change as a result.

|

"The mere fact of investigations is already affecting the market. It influences investors, venture capitalists, and innovators." |

In dynamic sectors such as manufacturing, larger companies often seek to acquire emerging technologies that could help them survive disruptive change. “But it’s these transactions that are now more likely to get a harder look from regulators,” notes Johnson. Take the automotive industry, where investors are pouring billions into startups making the next generation of electric and autonomous technologies. Antitrust enforcers will likely look harder for possible killer acquisitions in this space, because today’s maker of parts and systems for these vehicles could be tomorrow’s major automaker.

The investigations will also have a big impact in the area of data, because “there’s no business in any sector that doesn’t have a data component that could be affected by these investigations or rulemakings,” notes Murray. Companies that own or control data in ways that could foreclose competition can expect greater scrutiny. “If your customer or competitor claims that you are using data in a way that is harmful to them, they have a really attentive audience at the agencies,” says Gilman. “There’s a dedicated staff at the FTC focused on how data issues should be analyzed and argued in an antitrust case.”

Antitrust analysis already considers data a competitive asset, and the European Commission has developed a framework to analyze the value of data, notes Thomas De Meese, an antitrust partner in Crowell & Moring’s Brussels office. The coming year could even see a revival in the U.S. or Europe of some version of the “essential facilities” doctrine, which says that a company could be required to license data at fair and reasonable terms if access to that data is deemed essential for creating a product and service for which there is a clear consumer demand.

The essential facilities doctrine was cited nearly 40 years ago in a decision forcing the phone company to give competitors access to its network, notes Smith. While the doctrine has not been cited favorably in recent times, the question is whether it might be used, for example, to force a manufacturer to share the data necessary for a software developer to develop an app for its vehicles or appliances. Or perhaps require a platform to ensure that other firms’ products and services can interoperate with its platform.

“But for most companies that are considering ways to monetize data, the main concern is to stay in compliance with privacy laws,” Kimmel says. “Data is likely to generate antitrust risk primarily for dominant firms with control of relatively unique data sets.”

“Regardless of whether you’re heavily invested in data or plat- forms, virtually every company will be affected by this new era of antitrust scrutiny,” says Murray. “That’s why it’s important to keep abreast of developments and evaluate which side of these emerging battle lines you fall on. Consider whether the emergence of new theories of competitive harm—or new rules regarding privacy—will have a positive or negative effect on your business, and then consider advocating with the appropriate agencies or politicians for or against the change.”

Meanwhile, today’s antitrust enforcers are increasingly well briefed and well resourced. As a result, executives need to be thinking harder about whether business practices or M&A activity could raise antitrust concerns, experts say. Could your data be misused to foreclose market opportunities for competitors? Could a transaction squelch current or future competition? Are your competitors employing such tactics, and should they be brought to the attention of state or national agencies? “Before presenting a deal to regulators, companies should be ready to anticipate and respond to these kinds of inquiries,” Gavil says.

“The coming changes are likely to create significant risks and opportunities for business depending on where they stand in the marketplace,” Kimmel adds. “To prepare, businesses should be thinking ahead—because now the enforcers certainly are.”

Swift Action in the EUIn September, Danish politician Margrethe Vestager won an unprecedented second five-year term as the European Union’s competition commissioner; she will also take charge of EU digital policy. “The EC has already levied billion dollar fines on one Big Tech platform, and Vestager’s return virtually ensures the continuity of the commission’s aggressive approach,” says Crowell & Moring’s Thomas De Meese. In October, Vestager ordered a chipmaker to immediately halt potentially anticompetitive practices while an investigation was underway. It was the first time in 18 years the commission had employed its powers to impose “interim measures.” With formal investigations requiring several years, the commission is acknowledging the need to take action before competitive damage is irreversible, De Meese says. Vestager has signaled she intends to use interim measures more widely. In their investigations, European authorities will take a particular interest in anticompetitive use of data and “dual-use” platforms, De Meese says. European authorities can still have a big impact on American companies. Beyond levying fines, their orders to cease or change infringing behaviors can effectively force global changes on companies that develop products for a global market. “European enforcers are poised for greater impact than their U.S. counterparts because the EU’s competition law standards are more favorable to plaintiffs or the government, especially for cases of dominant-firm behavior,” notes Crowell & Moring’s Lisa Kimmel. |

|

"The EC has levied billion-dollar fines on one Big Tech platform. Vestager's return virtually ensures the continuity of their aggressive approach." |

Antitrust on the Rise

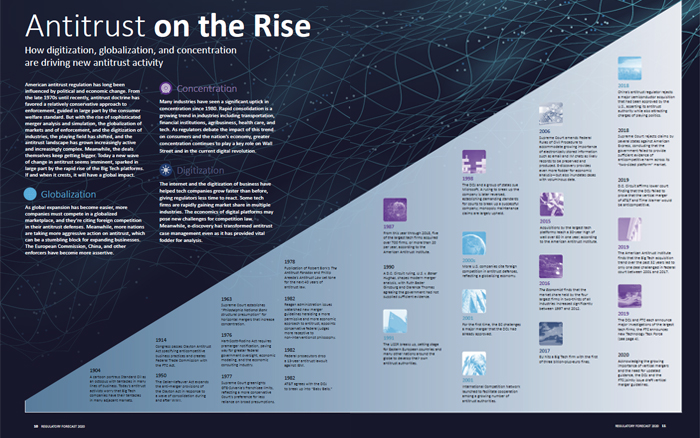

How digitization, globalization, and concentration are driving new antitrust activity

American antitrust regulation has long been influenced by political and economic change. From the late 1970s until recently, antitrust doctrine has favored a relatively conservative approach to enforcement, guided in large part by the consumer welfare standard. But with the rise of sophisticated merger analysis and simulation, the globalization of markets and of enforcement, and the digitization of industries, the playing field has shifted, and the antitrust landscape has grown increasingly active and increasingly complex. Meanwhile, the deals themselves keep getting bigger. Today a new wave of change in antitrust seems imminent, sparked in large part by the rapid rise of the Big Tech platforms. If and when it crests, it will have a global impact.

Globalization

As global expansion has become easier, more companies must compete in a globalized marketplace, and they’re citing foreign competition in their antitrust defenses. Meanwhile, more nations are taking more aggressive action on antitrust, which can be a stumbling block for expanding businesses. The European Commission, China, and other enforcers have become more assertive.

Concentration

Many industries have seen a significant uptick in concentration since 1980. Rapid consolidation is a growing trend in industries including transportation, financial institutions, agribusiness, health care, and tech. As regulators debate the impact of this trend on consumers and the nation’s economy, greater concentration continues to play a key role on Wall Street and in the current digital revolution.

Digitization

The internet and the digitization of business have helped tech companies grow faster than before, giving regulators less time to react. Some tech firms are rapidly gaining market share in multiple industries. The economics of digital platforms may pose new challenges for competition law. Meanwhile, e-discovery has transformed antitrust case management even as it has provided vital fodder for analysis.

- 1904: A cartoon portrays Standard Oil as an octopus with tentacles in many lines of business. Today’s antitrust activists worry that Big Tech companies have their tentacles in many adjacent markets.

- 1914: Congress passes Clayton Antitrust Act specifying anticompetitive business practices and creates Federal Trade Commission with the FTC Act.

- 1950: The Celler-Kefauver Act expands the anti-merger provisions of the Clayton Act in response to a wave of consolidation during and after WWII.

- 1963: Supreme Court establishes “Philadelphia National Bank structural presumption” for horizontal mergers that increase concentration.

- 1976: Hart-Scott-Rodino Act requires premerger notification, paving way for greater federal government oversight, economic modeling, and the economic consulting industry.

- 1977: Supreme Court greenlights GTE-Sylvania’s franchisee limits, reflecting a more conservative Court’s preference for less reliance on broad presumptions.

- 1978: Publication of Robert Bork’s The Antitrust Paradox and Phillip Areeda’s Antitrust Law set tone for the next 40 years of antitrust law.

- Reagan administration issues watershed new merger guidelines heralding a more permissive and more economic approach to antitrust; appoints conservative federal judges more receptive to non-interventionist philosophy.

- 1982: Federal prosecutors drop a 13-year antitrust lawsuit against IBM.

- 1982: AT&T agrees with the DOJ to break up into “Baby Bells.”

- 1987: From this year through 2018, five of the largest tech firms acquired over 700 firms, or more than 20 per year, according to the American Antitrust Institute.

- 1990: A D.C. Circuit ruling, U.S. v. Baker Hughes, shapes modern merger analysis, with Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Clarence Thomas agreeing the government had not supplied sufficient evidence.

- 1991: The USSR breaks up, setting stage for Eastern European countries and many other nations around the globe to develop their own antitrust authorities.

- 1998: The DOJ and a group of states sue Microsoft. A ruling to break up the company is later reversed, establishing demanding standards for courts to break up a successful company; monopoly maintenance claims are largely upheld.

- 2000s: More U.S. companies cite foreign competition in antitrust defenses, reflecting a globalizing economy.

- 2001: For the first time, the EC challenges a major merger that the DOJ had already approved.

- 2001: International Competition Network launched to facilitate cooperation among a growing number of antitrust authorities.

- 2006: Supreme Court amends Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to accommodate growing importance of electronically stored information such as email and IM chats as likely records to be preserved and produced. E-discovery provides even more fodder for economic analysis—but also inundates cases with voluminous data.

- 2015: Acquisitions by the largest tech platforms reach a 30-year high of well over 60 in one year, according to the American Antitrust Institute.

- 2016: The Economist finds that the market share held by the four largest firms in two-thirds of all industries increased significantly between 1997 and 2012.

- 2017: EU hits a Big Tech firm with the first of three billion-plus-euro fines.

- 2018: China’s antitrust regulator rejects a major semiconductor acquisition that had been approved by the U.S., asserting its antitrust authority while also attracting charges of playing politics.

- 2018: Supreme Court rejects claims by several states against American Express, concluding that the government failed to provide sufficient evidence of anticompetitive harm across its “two-sided platform” market.

- 2019: D.C. Circuit affirms lower court finding that the DOJ failed to prove that the vertical merger of AT&T and Time Warner would be anticompetitive.

- 2019: The American Antitrust Institute finds that the Big Tech acquisition trend over the past 32 years led to only one deal challenged in federal court between 2001 and 2017.

- 2019: The DOJ and FTC each announce major investigations of the largest tech firms; the FTC announces new Technology Task Force.

- 2020: Acknowledging the growing importance of vertical mergers and the need for updated guidance, the DOJ and the FTC jointly issue draft vertical merger guidelines.

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26