European TMT & Privacy Bulletin - January 2013

Client Alert | 42 min read | 01.22.13

Sections of this issue:

Electronic Communications & IT

- Can the Private Copy Obtained from an Illegal Source Be Legal?

- Court of Justice Rules on Resale of Computer Software

Privacy & Data Protection

Contracts & E-Commerce

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS & IT

Can the Private Copy Obtained from an Illegal Source Be Legal?

On September 21, 2012, the Dutch Supreme Court asked the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) for a preliminary ruling in the case of ACI vs Stichting De Thuiskopie regarding the interpretation of the private copying exemption laid down in Article 5(2) of the EU Copyright Directive. The CJEU was asked among others things to clarify whether the private copying exemption also applies to private copies obtained from illegal sources. If not, the Dutch Supreme Court asked the CJEU to indicate whether the Member States may nevertheless take private copies coming from an illegal source into account for determining the fair compensation to be divided among the copyright holders.

I. Background

1) According to Article 5(2) of the EU Copyright Directive1, Member States may provide for exceptions or limitations to the reproduction right laid down in Article 2 of the same Directive. Article 5(2)(b) of the EU Copyright Directive, in particular, deals with the exemption for private copies, being reproductions on any medium made by a natural person for private use and for purposes that are neither directly nor indirectly commercial, on condition that the right holders receive a fair compensation. Article 5(5) of the EU Copyright Directive furthermore provides the so-called 'three-steps-test', being the three conditions to be fulfilled by any exception or limitation to the rights of the copyright holder: exceptions or limitations shall only be applied in certain special cases (step 1), which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work or other subject matter (step 2) and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder (step 3).

In the Netherlands, manufacturers and importers of mediums (e.g. clean CD's and DVD's) pay for the fair compensation by means of levies imposed on their products (Article 16c(2) of the Dutch Copyright Act). The level of remuneration is determined by the Dutch public organization called 'Stichting De Thuiskopie', which moreover divides the revenues among all copyright holders.

2) The dispute at hand existed between the 'Stichting De Thuiskopie' and several manufacturers and importers of mediums (among others ACI) and concerns the question whether the private copying exemption in the Dutch Copyright Act applies to private copies obtained from illegal sources and whether the Dutch Copyright Act foresees to compensate copyright holders for such copies.

Both the Dutch Court of Appeal and the Advocate-General Mr. Huydecoper at the Dutch Supreme Court found that the Dutch Copyright Act does not differentiate private copies on the basis of their sources and therefore should apply to copies from illegal sources as well.

II. The Dutch Supreme Court's judgment of September 21, 2012

3) In its judgment of September 21, 2012, the Dutch Supreme Court however ruled that the interpretation of Article 5(2) of the EU Copyright Directive is decisive in the present case. Therefore the Dutch Supreme Court referred the following three questions to the CJEU:

1) Does the private copying exemption laid down in Article 5(2), read in conjunction with Article 5(5) of the EU Copyright Directive, apply to private copies, regardless of the source of those copies? Or should these copies be obtained from an authorized source?

2) The second question is divided in two parts:

a) If the private copies should originate from authorized sources, then can the so-called 'three-steps-test' provided for in Article 5(5) of the EU Copyright Directive be a ground for extension of the scope of the exception foreseen in Article 5(2), or can the application of Article 5(5) only lead to a restriction of the scope of the exception foreseen in Article 5(2)?

b) If the private copies should originate from authorized sources, then is the national rule imposing that private copies should be fairly compensated, regardless of the question whether these copies are made in conformity with Article 5(2) of the EU Copyright Directive, and on condition that such national rule does not violate the copyright holder's right to prohibit such reproductions and its right to compensation of the damages incurred, in line with Article 5 of the EU Copyright Directive or any other rule of European Union law? In this respect the Dutch Supreme Court also enquired whether the fact that technical facilities to counter unauthorized private copies are not (yet) available has to be taken into consideration.

3) Is Article 14 of the Enforcement Directive2 applicable to a case like this?

III. The expected judgment of the CJEU

4) The expected judgment of the CJEU in the present case could be of great importance for the fair compensation of all copyright holders in the European Union, given the scale of private copies originating from illegal sources nowadays and the fact that technical facilities to counter these unauthorized private copies are not (yet) available.

The next step in the proceedings before the CJEU will be the opinion of the Advocate-General. The proceedings can be expected to take approximately 2 years. To be continued...

Offering blank DVD's for sale on "eBay"... mind your obligation to contribute to the fair compensation for private copying! In its judgment of October 4, 2012, the Belgian Supreme Court held that a person offering blank DVD's for sale on "eBay" falls within the third category of importers or purchasers within the meaning of Article 1 of the Belgian Royal Decree of 28 March 1996 regarding the remuneration for private reproduction, regardless whether the activity of offering such mediums for sale is the main or core activity of the person concerned.

According to Article 55, §1 of the Belgian Act on Copyright and Neighboring Rights of 30 June 1994 (Belgian Copyright Act) authors, performers and producers of phonograms and audiovisual works are entitled to remuneration for the private reproduction of their works and performances. Pursuant to the second paragraph of the same provision, this remuneration must be paid by the manufacturer, importer or intra-community purchaser of media that can be used to reproduce sounds and audiovisual works and/or of appliances permitting such reproduction. The payment should be made upon the placing on the market of such media and such appliances on the national territory.

Article 1, 11°, 12° and 13° of the Royal Decree of 28 March 1996 regarding the right to remuneration for the private reproduction for the works of authors, performers and producers of phonograms and audiovisual works defines three categories of importers and intra-community purchasers: firstly the exclusive importers and intra-community purchasers having an exclusive right to distribute such media on the national territory, secondly the wholesale importers and intra-community purchasers having as their main or core activity to offer such media to other distributors and thirdly the other importers and intra-community purchasers which are not exclusive nor wholesale.

Pursuant to Article 3, §§1 and 3 of the same Royal Decree the remuneration for private reproduction is due at the moment of putting the media on the national market, which corresponds to – as far as the third category of importers or intra-community purchasers are concerned – the importation or intra-community purchase of one or more media.

The Belgian Supreme Court finds that it follows from these provisions that a remuneration for the private reproduction is also due by an intra-community purchaser(not exclusive nor wholesale), even if the offer of such media for sale to customers is not its core or main activity. Therefore, the Belgian Supreme Court annulled the judgment of the Brussels Court of Appeal of 21 December 2010 finding that the defendant offering blank media for sale on "eBay" did not fall within any of the three categories of importers or intra-community purchasers.

According to the Belgian Supreme Court the act of offering blank media for sale on "eBay" thus falls within the scope of the third category of importers or intra-community purchasers for which remuneration for the private reproduction is due.

1Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonization of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (EU Copyright Directive).

2 Directive 2004/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the enforcement of intellectual property rights.

For more information, contact: Sofie Cubitt

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS & IT

Court of Justice Rules on Resale of Computer Software

On 3 July 2012, the Court of Justice ruled on a preliminary reference of the Bundesgerichtshof with regard to the resale of computer software. The Court ruled that computer programs can be resold and the buyers are lawful acquirers, on the condition that the program is made unusable on the first acquirer's server, and that all the subsequent acquirers are lawful acquirers.

The background of the case and the questions referred to the Court

Oracle distributes 85% of its computer software through downloading of the program from the internet. The user rights include the right to store a copy of the program permanently on a server and to grant a certain number of users access by downloading on their computers. The accompanying maintenance agreements allow for the downloading of updates of the program.

UsedSoft markets used software licenses, by acquiring licenses, or parts of them, from customers and reselling them. UsedSoft promoted an 'Oracle Special Offer', offering for sale used licenses for Oracle programs. UsedSoft customers that buy such a used license download a copy of the program directly from Oracle's website. Customers who already have the software and purchase additional licenses are induced by UsedSoft to copy the program to the work stations of the additional users.

Oracle brought proceedings before the Landgericht in Munich seeking an order that UsedSoft cease the above described practices. UsedSoft's appeal against the admissibility of the application by the Landgericht was dismissed. UsedSoft then appealed to the Bundesgerichtshof. This Court submitted three prejudicial questions to the European Court of Justice on the application of paragraph 69d(1) of the UrhG, which transposes Article 5(1) of Directive 2009/24:

1) Is the person who can rely on exhaustion of the right to distribute a copy of a computer program a "lawful acquirer" within the meaning of Article 5(1) of Directive 2009/24?

2) Is the right to distribute a copy of a computer program exhausted in accordance with the first half-sentence of Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24 when the acquirer has made the copy with the right holder's consent by downloading the program from the internet onto a data carrier?

3) If the reply to the second question is also in the affirmative: can a person who has acquired a "used" software license for generating a program copy as "lawful acquirer" under Article 5(1) and the first half-sentence of Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24 also rely on exhaustion of the right to distribute the copy of the computer program made by the first acquirer with the right holder's consent by downloading the program from the internet onto a data carrier if the first acquirer has erased his program copy or no longer uses it?

The Court's answers

The Court answers that downloading a copy of a computer program and concluding a user license agreement for that copy form an invisible whole. It rules that Oracle's right of ownership of the copy is transferred since the customers can use the copy for an unlimited period in return for a fee. It is irrelevant that the copy was made available by means of a download to conclude that it constitutes a 'first sale of a copy of a program' within the meaning of Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24. The Court adds that a broad interpretation of 'sale' is necessary not to undermine this Article, since suppliers would otherwise merely have to call a contract a 'license' to prevent a transfer of ownership.

The Court also points out that Directive 2009/24 is a lex specialis, so that making available a copy for download does not constitute 'making it available to the public' within the meaning of Article 3(1) of Directive 2001/29. This means that the right of distribution is not exhausted based on article 3(3).

The Court confirms that Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24 applies to intangible copies. The argument that Directive 2001/29, that harmonizes certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, only refers to tangible objects is not accepted. The Court states that the European Union had a different intention with Directive 2009/24, since Article 1(2) of this lex specialis states that the Directive applies to any form of computer program. The Court also added that, from an economic point of view, the distinction should not be made between tangible objects and intangible copies.

The Court moreover rules that the fact that the original copy is corrected, altered or functionalities are added based on the maintenance agreements, does not prevent the exhaustion of the distribution right of the copy, as the updates should be deemed an integral part of the original copy.

As a result, downloading of a copy of a computer program from the internet, authorized by the author exhausts the right of distribution of this copy in the EU within the meaning of Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24.

Next, the Court answers the first and the third questions jointly, namely whether and under what conditions an acquirer of used licenses is a 'lawful acquirer' within the meaning of Article 5(1) of Directive 2009/24 as a result of the exhaustion of the distribution right of Article 4(2) of this Directive.

The Court rules that downloading a copy of a purchased computer program onto a computer is an authorized reproduction, so that the first acquirer is a 'lawful acquirer' of the copy. The first sale thus exhausts the copyright holder's distribution right.

The Court rules that the second acquirer of the license, and all subsequent acquirers, can rely on the exhaustion of the distribution right of the author under Article 4(2) of Directive 2009/24, and thus have to be regarded lawful acquirers of the copy under Art. 5(1) of this Directive. It states that, if the author would be able to rely on its exclusive reproduction right of Art. 4(2) of Directive 2009/24 to prevent this, it would render ineffective the exhaustion of the distribution right.

The Court, however, rules that the first acquirer cannot divide the license if it relates to more users than he needs, as he has to make his copy unusable upon resale to avoid infringing the author's exclusive right of reproduction. This is also the case when the acquirer of additional rights already has a copy of the program. It holds that the copyright holder is entitled to ensure by all means at his disposal that the copy is made unusable.

Conclusion

The answers of the Court of Justice allow the resale of licenses of computer programs when the copy of the program has to be downloaded from the initial seller's website. The reseller can however not sell more than he owns. He has to make his own copy unusable at the time of the resale. A license cannot be divided. The resale of parts of licenses is not allowed.

For more information, contact: Emmelie Wijckmans

PRIVACY & DATA PROTECTION

EU Commission's proposal for a new Data Protection Regulation - Status

As mentioned in our previous newsletters, on January 25, 2012, the EU Commission has proposed a comprehensive reform of existing EU data protection rules, including a draft for a new Data Protection Regulation.

This proposal is the subject of the ordinary legislative procedure, which means it is under review by both the Council and the European Parliament as the draft has to be approved by both the European Parliament and the Council in order to become law.

The Committee for Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) has been appointed as the main committee with responsibility for the draft Regulation in the European Parliament. LIBE has already published three working documents and has published a calendar with dates of several meetings, workshops, and hearings that will be organized until the vote in plenary. MEP Jan Philipp Albrecht, rapporteur for LIBE, has meanwhile published a draft report holding more than 200 pages of suggested amendments to the proposed Regulation. A second exchange of views will be held on the draft report in the LIBE meeting on January 21, 2013. Without entering into the details at this stage - as the report is still not final - the report (with some exceptions) does not seem to take into account criticism and concerns of businesses with respect to the draft Regulation and, if adopted, the amendments will make the new regime even stricter for businesses. It is still anticipated that by the summer of 2013, the Regulation should be ready for a trilogue with the Council and the Commission, and that the Regulation shall be put to a vote in the plenary session of the European Parliament by early 2014.

The Working Party on Information Exchange and Data Protection (DAPIX) handles the review of the draft Regulation in the Council. It has scheduled an article by article review. On December 3, 2012, a Report on the progress achieved under the Cyprus Presidency was published. DAPIX has reviewed 4 of the 11 Chapters of the draft Regulation.

The proposal is also evaluated by national parliaments. An overview thereof can be found here.

Below are some of the various elements of the proposal that are under discussion:

1) The fundamental choice of a Regulation instead of a Directive. During an October 25, 2012, meeting of the Council, among others, the choice of legal instrument was discussed. Some delegations expressed their preference for a Directive - which needs to be implemented afterwards by each Member State, so that there is a risk of, again, having 27 different national laws - whereas others follow the Commission in the choice for a Regulation which has direct effect in all Member States. In a December 4, 2012 speech ("The overhaul of EU rules on data protection: making the single market work for business"), Commissioner Reding has made it clear that in her view the decision to propose a Regulation was the right one beyond any doubt because it meets the expectations of business to have a true digital single market with one single law for data protection.

It is our opinion that a Regulation will provide businesses operating in various Member States a much higher legal certainty, which, in combination with the "one-stop-shop" principle (the national data protection authority of the place where the controller or processor has its main establishment would supervise the activities of the controller or processor in all Member States), can only be welcomed as it would reduce administrative formalities, saving time and money (acknowledging that some of the novelties in the draft may on the other hand increase costs for businesses). Having 27 different national data protection laws in this digital age, is something that should be avoided.

2) Delegated and implementing acts. Delegated acts allow Parliament and the Council to delegate to the Commission the power to adopt "non-legislative acts of general application to supplement or amend certain non-essential elements of a legislative act." In the proposal for the new Regulation, a considerable amount of delegated and implementing acts has been foreseen.

In her above mentioned speech, Commissioner Reding has already confirmed that there may be some changes to the draft in this respect and that, in lieu of these acts, several different solutions have been considered. These include (i) more detail in the text of the Regulation, (ii) allowing the consistency mechanism to step in (i.e. the mechanism under article 57 of the draft Regulation for co-operation between the supervisory authorities and the Commission in order to ensure the consistent application of the Regulation throughout the Union), (iii) allowing codes of conduct and other business-lead initiatives or (iv) just deleting certain acts in their entirety.

The Commission has also already indicated that where a delegated or implementing act was proposed, the exercise of this power could be further qualified in three ways (source: Report on the progress achieved under the Cyprus Presidency):

1) by inserting procedural rules in the empowerment, for example as regards specific consultation arrangements to be followed by the Commission;

2) by putting substantive conditions on the empowerment; or

3) by limiting the scope of the empowerment.

3) The so-called SME exception to some of the obligations for small and medium-sized enterprises (i.e. companies employing less than 250 employees). The criticism here is that this SME exception is not an optimal solution in all cases, as obligations aimed at ensuring an appropriate level of data protection, should not necessarily be differentiated only by reference to the number of employees employed by the company. Hence, the question is whether the risk inherent in certain data processing operations should not be the main criterion for evaluating the applicability of data protection obligations: where the data protection risk is higher, more detailed obligations would be justified.

4) The right to be forgotten. The Vice President of the European Parliament, Alexander Alvaro, said the provision in the draft Regulation guaranteeing individuals the right to be forgotten needs to be limited. He said this right "has to be limited to the point where we're talking about judicially, clearly examined, illegal violations of rights."

These are just a few examples of the ongoing discussions. The Commission meanwhile tries to bring the discussions back to its essence by publishing on its website the interesting contribution "Myth-busting: what Commission proposals on data protection do and don't mean," which can be accessed here.

For more information, contact: Frederik Van Remoortel

CONTRACTS & E-COMMERCE

Implementation of new provisions on consumer protection subject of public consultations

The Belgian telecom regulator (BIPT/IBPT) launched several consultations with respect to draft legislation implementing the new provisions on consumer protection in the Belgian Telecom Act. On October 17, 2012, the regulator organized a consultation on the draft Royal Decree specifying the content of information cards to be published by the operators regarding their services. On November 21, 2012, the regulator launched a consultation on its draft resolution regarding the requirements and format of notifications following unilateral contractual modifications by operators.

I. Background

1) With the Act of 10 July 2012, the Belgian legislator modified the Act of 13 June 2005 on electronic communication ("Telecom Act"). In accordance with the modified article 108 §2, the regulator can specify the situations in which a notification must be sent to the consumer in case of unilateral contractual modifications by the operator, and the format thereof. The new article 111 §2 of the Telecom Act provides that operators place an information card at the consumer's disposal for each service that they commercialize. The legislator hereby implemented article 20.2 and article 21.1 of the Universal Service Directive 2002/22/EC, modified by Directive 2009/136/EC. Similar modifications were introduced in the Act of 15 May 2007 on consumer protection with respect to broadcasting services.

2) On November 21, 2012, the regulator launched a consultation on its draft resolution regarding the requirements and format of notifications within the meaning of article 108 §2 of the Telecom Act and article 6 §2 of the Act of 15 May 2007. Earlier, on October 17, 2012, the regulator also organized a consultation on the draft Royal Decree specifying the content of the information cards in the meaning of article 111 §2 of the Telecom Act and article 5 §2 of the Act of 15 May 2007.

II. Highlights

3) We hereby summarize the highlights of the consultations as published by the regulator:

With respect to the notification obligation:

- A notification must be sent in the event of any proposed contractual modification, both to the detriment and to the benefit of the subscriber, unless there can be no reasonable doubt as to the acceptance of the modification by the subscriber;

- The notification, and the right to terminate the contract free of charge, is henceforth also required in the event of a contractual price indexation;

- The notification must specify both the modifications that are proposed and the right to terminate the contract free of charge;

- The ‘individual' nature of the notification implies that a reference to a website, press communication or customer service in order to obtain the information regarding the modification and the right to terminate the contract free of charge, does not suffice;

- The notification must mention (i) the date on which the modifications will enter into force, (ii) a summary of the content of the contractual clauses as drafted prior to and after the modification and (iii) the right to terminate the contract free of charge;

- The information must be provided in an objective, complete, understandable and precise manner. The right to terminate the contract free of charge must be mentioned in bold and in a box separate from the text;

- Examples of the different formats of the notification are included in the consultation.

With respect to the information card:

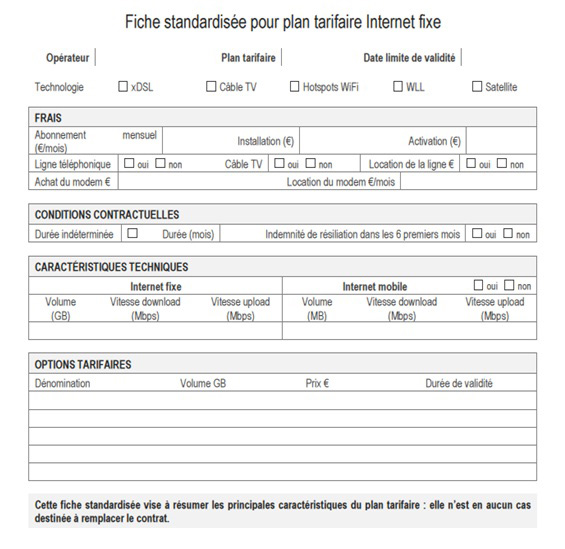

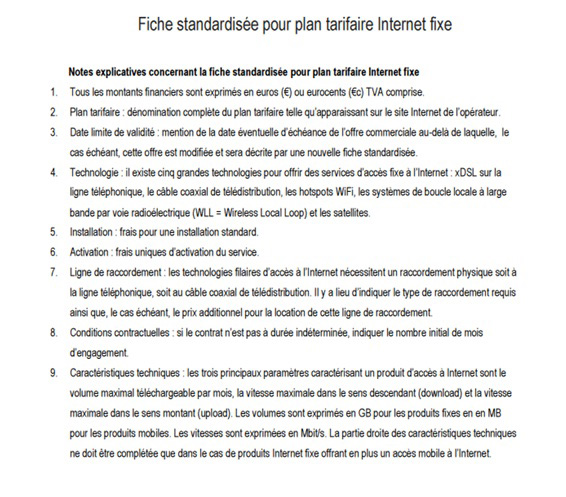

- The draft Royal Decree contains seven versions of the information card depending on the type of product offered to the end user: (i) fixed telephony, (ii) mobile postpaid services, (iii) mobile prepaid services, (iv) fixed internet access, (v) mobile internet access, (vi) television services and (vii) bundled packs;

- The information card covers one A4-sheet (with the exception of the card for bundled tariff plans). The recto side holds the essential characteristics of the service such as tariffs, duration of the contract, technical specifications such as download and upload speeds etc., the verso side holds an explanation of the elements mentioned on the recto side;

- A new version of the information card must be published in the event of temporary promotional offers. The card must explicitly mention the period during which the promotional offer is valid;

- The information cards must be available in all points of sale and on the operator's website;

- Advertising cannot be attached to the information card;

- As an example, we attach the draft template of the information card for fixed internet services below;

Draft template for fixed internet services:

Recto side:

Verso side:

For more information, contact: Karel Janssens

Contacts

Insights

Client Alert | 6 min read | 02.24.26

Artificial Intelligence and Human Resources in the EU: a 2026 Legal Overview

The year 2026 marks a major regulatory turning point for European companies using or considering the use of artificial intelligence in their human resources (HR) processes. The Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 on artificial intelligence (the AI Act) is entering a critical implementation phase, while the European Commission's "Digital Omnibus" package will clarify several obligations and modify certain deadlines.

Client Alert | 3 min read | 02.24.26

DOJ v. OhioHealth Confirms Antitrust Enforcers’ Continued Focus on Health Care Markets

Client Alert | 4 min read | 02.24.26

Client Alert | 4 min read | 02.24.26

State-Level Merger Control Grows: California Joins “Mini-HSR” Trend with Senate Bill 25