E-Discovery - Reining in E-Discovery

Publication | 01.19.16

A number of changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure took effect in December 2015 that promise to reshape, and rationalize, some fundamental aspects of e-discovery in federal litigation.

These changes address the increasing discovery challenges created by ever-growing amounts of electronic information. “Today, the cost of discovery can sometimes outweigh the potential value of the claims in the case,” says Jeane Thomas, chair of Crowell & Moring’s E-Discovery & Information Management Group.

The revised rules include two key changes on that front:

- Redefining what material is discoverable(Rule 26(b)(1)): Traditionally, discovery has been permitted for anything that is “relevant”—a broad term that often led to unreasonably costly efforts. The new rule says that such requests need to be “proportional” as well. Requests need to consider factors such as the importance of the discovery to resolving the issues at stake, the amount in controversy, and whether the burden or expense of discovery outweighs its benefits. In short, instead of broad requests for information, parties now need to draft targeted requests that are proportional and reasonable.

- Clarifying spoliation sanctions (Rule 37(e)): Courts have varied in their approach to sanctions when parties destroy discoverable information, with some taking a hard line. Even when spoliation has been unintentional, says Thomas, “some courts have given the jury adverse inference instruction, basically saying they should assume that the deleted information would have been harmful to the spoliating party’s case. That’s often a case-determinative sanction.” As a result, she adds, “companies stopped deleting information altogether to avoid the risk of sanctions, increasing the cost and complexity of discovery.”

Under the new rules, spoliation resulting from unintentional negligence no longer warrants severe sanctions. “They can be imposed only when the court finds that the party destroyed evidence intentionally to keep the other party from using it.” This reduced risk of sanctions, she says, “enables companies to implement sound information governance policies that include the routine destruction of electronically stored information—to avoid the costs associated with over-preservation.”

The revised rules simplify matters for companies responding to discovery requests—but they also place new responsibilities on those companies. Traditionally, responses to discovery requests have been broad “boilerplate” objections followed by lengthy negotiations, but that is no longer sufficient. “With amendments to Rule 34(2)(B) and (C), the responding party has to state specifically what it is objecting to in the request, what it is going to produce, and the date it will produce it by—all within 30 days of receiving the request,” says Thomas. “That means that law departments need to have a litigation-response plan ready and quickly understand the scope of what they likely will need to produce—because you can no longer wait six to nine months to figure it out.”

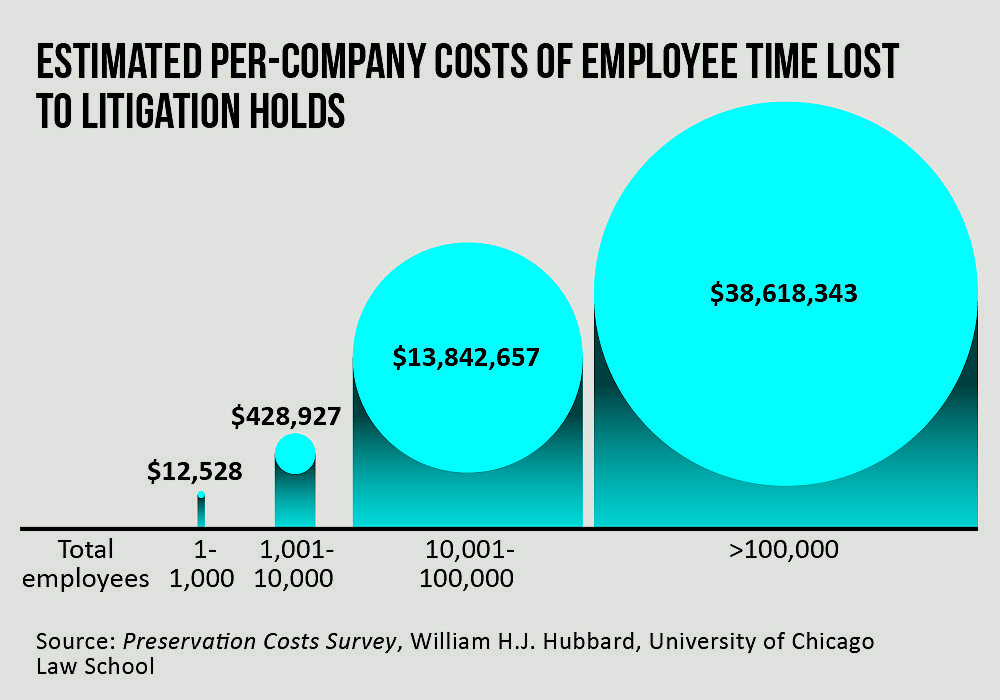

[The need to preserve documents for discovery places a number of growing burdens on companies—including the cost of large amounts of employee time.]

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.01.26

Publication | 02.19.26

The QICDRC Practice Direction on the Use of Artificial Intelligence

Publication | 02.06.26