The NLRB’s One-Two Punch Gives Unions a Significant Boost

Client Alert | 21 min read | 09.08.23

The NLRB recently effected two significant, pro-union changes to the way in which future union organizing and representation cases proceed. First, abandoning more than 50 years of settled law, the National Labor Relations Board’s recent decision in Cemex Construction Materials Pacific (372 NLRB No. 130), changed the way in which unions will likely organize private sector employers in the United States. Pursuant to Cemex, if a union claims to have majority support and demands recognition, an employer must either (1) grant recognition without the benefit of an NLRB election, or (2) file its own NLRB petition seeking an election. If the employer fails to take either step, the union can file an unfair labor practice charge, and the NLRB will find a violation and order mandatory union recognition unless the employer proves the union did not have majority support in an appropriate bargaining unit. And even if the employer files a petition for election (an “RM petition”), the NLRB may cancel the election and issue a bargaining order if the employer commits virtually any unfair labor practice during the period preceding the election.

Second, on August 24, 2023, the NLRB announced its long-awaited Final Rule, overturning significant portions of the Final Rule adopted by the Trump Board, and returning to expedited election timelines long thought to favor unions. When the Final Rule becomes effective on December 26, 2023, employers will have less time to prepare for elections following the filing of an election petition.

Taken together, these changes fundamentally alter the manner in which employers will need to prepare for and respond to union organizing and demands for voluntary recognition.

I. The Cemex Decision:

In Cemex, which was issued on August 25, 2023 over a strong dissent, the NLRB uprooted more than 50 years of settled Board law and fundamentally altered the process by which employees can (and likely will) unionize. For decades, employers could lawfully reject union demands for voluntary recognition and could require that unions file a petition for an election. In Cemex, the Board turned that decades-old paradigm on its head and created new obligations and potential liability for employers who face union demands for recognition. Employers now have three options when confronted with a demand for recognition.

- Grant Voluntary Recognition: An employer can recognize the union, foregoing the opportunity to ensure the union has majority support through an NLRB-administered secret-ballot election;

- File an RM Petition for Election: An employer can seek an election by filing an “RM petition” with the NLRB “promptly” (i.e., within two weeks of the union’s demand for recognition) to test the union’s majority support and/or challenge whether the employees the union seeks to represent constitute an appropriate bargaining unit. If the employer fails to file an RM petition, it will lose the ability to seek an election; or

- Take No Action: An employer can elect to do nothing in response to a union demand for recognition, neither recognizing the union nor filing an RM petition, but will do so at its peril. If an employer does nothing, a union can file an unfair labor practice (“ULP”) charge claiming that the employer unlawfully refused to bargain by rejecting its demand for recognition. If the employer fails to prove that the union lacks majority support or that the proposed bargaining unit is inappropriate in the ULP proceeding, the employer will be deemed to have engaged in an unlawful refusal to bargain, and the Board will issue a remedial bargaining order. In addition, if the employer implements changes to mandatory subjects of bargaining unilaterally after the union’s demand for recognition, that will constitute grounds for a separate failure to bargain ULP charge and a likely bargaining order as well.

The first option reflects the current Board’s position that union claims of majority status based on signed union authorization cards are an accurate and reliable measure of employee support that should be accepted and acted upon immediately. As history has shown, however, employees often sign union authorization cards as a result of pressure from union organizers, based on misinformation or a lack of a full understanding of the ramifications associated with signing a union card. In effect, the Cemex decision creates a rebuttable presumption that a majority of employees would wish to be represented by a union, if allowed to vote in a secret ballot election, based solely on the union’s claim that its request for recognition is based on majority support.

The second option, while appearing to grant employers the opportunity to test their employee’s union sentiments in a secret-ballot election, may not be all that it appears. As an initial matter, the employer must file an RM petition within two weeks of the union’s demand for recognition or it will lose its right to an election. And as explained below, the Board’s aggressive new approach to bargaining orders will likely mean that employers will be deprived of the right to an election, even after filing an RM petition, if they engage in any violation of the NLRA following the union’s demand for recognition –even violations that would never have resulted in a bargaining order in the past.

The third option – doing nothing – is risky. As noted above, if an employer rejects a union’s demand and does not file a timely RM petition, the demanding union can file a ULP charge alleging that the employer failed to bargain in violation of the NLRA. The Board will find a violation and will issue a bargaining order unless the employer proves in the ULP proceeding that the union lacks majority support and/or the proposed bargaining unit is not appropriate. Additionally, an employer choosing option three may face additional liability for changes it makes to mandatory terms and conditions of employment that it has implemented following the union’s demand for recognition.

A New Standard for Bargaining Orders

The Cemex decision also ushered in an aggressive new policy regarding the use of bargaining orders, signaling that virtually any unfair labor practice finding following a union’s demand could result in the Board’s entry of a bargaining order (and cancellation of a possible election), even in cases in which the employer has filed an RM petition. This aspect of the Cemex decision is particularly problematic because the current NLRB has issued several decisions that have lowered the threshold for finding employer conduct unlawful, with more of the same sure to follow.

Since the Supreme Court’s decision in NLRB v. Gissel Packing Co., 395 U.S. 575 (1969), more than 50 years ago, the NLRB typically required a “rerun election” if an employer committed unfair labor practices during the critical period while an election was pending, reserving bargaining orders for cases in which unlawful conduct is so egregious that there was little possibility of erasing the effects of past practices and of ensuring a fair election. Gissel also required that bargaining orders be based on a case-specific analysis. Pursuant to the new standard announced in Cemex, the Board may issue a bargaining order based on a single unlawful statement or action, after a union’s demand for recognition, rendering the original petition and election results irrelevant, even if the union lost by a landslide.

A Recipe for Litigation, Uncertainty and Delay

The Board cites as one of the bases for its new approach the “strong statutory policy in favor of prompt resolution of questions concerning representation.” Yet, the approach the Board has adopted may result in more litigation and increased delay in several ways. First, if an employer does not recognize the union upon demand or file an RM petition, then the parties will be left to litigate the question concerning representation in an unfair labor proceeding from the outset, and the processing of representation cases typically takes precedence over the investigation and litigation of unfair labor practice cases.

Second, there is likely to be increased delay even if an employer decides to file an RM petition when faced with a demand for recognition, based on the new, watered-down standard for bargaining orders. Specifically, as noted above, the Board has now indicated a willingness to issue bargaining orders, and cancel scheduled elections or nullify election results, based on an employer’s unfair labor practices, or even a single unfair labor practice, that would never have resulted in the issuance of a bargaining order in the past. Given this new approach, unions now have an incentive to review every statement made or action taken by an employer following a demand for recognition and file ULP charges following a demand for recognition if, in the union’s view, any given statement or action might be construed as interfering with employees’ Section 7 rights.

Third, petitions for elections, whether filed by a union or employer, must include a definition of the specific bargaining unit at issue. By contrast, union demands for recognition often do not include a precise definition of the unit the union seeks to represent. The Cemex decision makes clear that employers may “challenge the appropriateness of the unit,” whether in a representation or ULP proceeding, but that assumes that unions seeking recognition have identified the unit in question. Some commentators have suggested that employers may have an advantage in such situations because they can file an RM petition that includes a definition of what they regard as the appropriate unit. In response, the union will be permitted to challenge the employers’ proposed unit definition, but under current Board law, will be required to prove why the employer’s petitioned-for unit is inappropriate. All of these issues have the potential to contribute to significant uncertainty and delay in the representation process.

Legal Challenges Likely

In a well-reasoned partial dissent, Board Member Kaplan criticized the majority’s opinion as both “unsound as a matter of policy and unenforceable as a matter of law.” Specifically, Kaplan argues that the Board’s Cemex decision is contrary to the Supreme Court’s decision in both Lincoln Lumber Div. Summer & Co. v. NLRB, 419 U.S. 301 (1974), which held that employers could lawfully reject union demands for recognition, and require the union to seek an NLRB election, and NLRB v. Gissel Packing Inc., 395 U.S. 575 (1969), reserving bargaining orders for the exceptional case or cases in which there are extensive unfair labor practices committed by the employer that cannot be effectively addressed through the NLRB’s traditional remedies. We anticipate that Member Kaplan is probably correct in predicting that application of the Cemex decision is likely to result in “lengthy litigation,” and it may not “survive judicial review.”

The Board’s New Final Rule Expedites the Union Election Timeline

In a further boost to unions, the NLRB adopted a Final Rule on August 24, 2023 that amended the procedures governing representation elections by requiring that union elections be held at the “earliest date practicable,” amongst other amendments limiting time for employers to challenge elections. The Final Rule will become effective on December 26, 2023, absent court intervention.

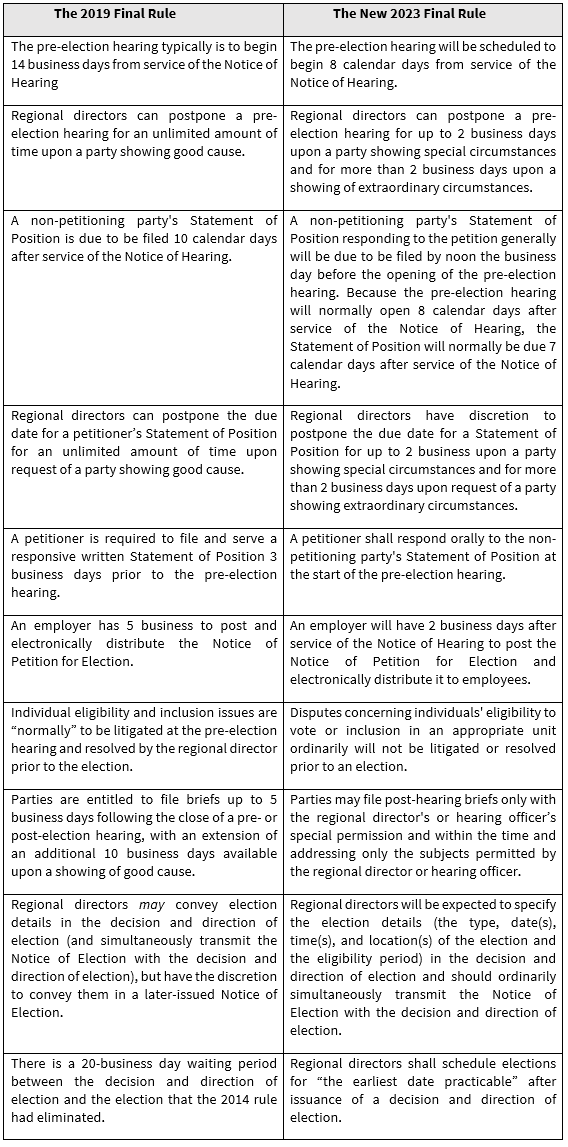

The new Final Rule largely guts the prior Rule promulgated by the Trump Board, and largely reinstates the election rules that were put in place in 2014 by the Obama Board by implementing the following changes, as summarized in the NLRB’s press release:

- Allowing pre-election hearings to begin more quickly;

- Ensuring that important election information is disseminated to employees more quickly;

- Making pre- and post-election hearings more efficient; and

- Ensuring that elections are held more quickly.

By way of background, the 2014 rule sped-up the election process, shortening the amount of time for employers to respond to union election petitions, thereby restricting employers’ ability to meaningfully challenge petitioned-for units. In 2019, the Trump Board unwound much of the prior 2014 rule by requiring a mandatory delay of at least 20 days between the date the NLRB issues a decision directing that an election be held, and the date of the election itself. The 2023 Final Rule amends the 2019 rule in the following ways:

In light of this Final Rule, employers should ensure they are aware of election timelines before a union demands recognition, and take steps to understand potential appropriate bargaining units, given the tight time frame between the filing of a petition and the hearing. Employers should be prepared to respond quickly – and lawfully – when faced with a petition and questions from their employees concerning representation.

Key Takeaways

- Going forward, employers can expect unions to claim majority support and demand recognition without filing for an election, forcing employers who are unwilling to agree to either file an RM petition or risk litigating the bona fides of the union’s claimed majority status and/or the appropriateness of the bargaining unit in a ULP proceeding, with the associated perils;

- Employers who chose to file an RM petition, or who reject union demands for recognition without doing so, will need to be extremely vigilant in seeking to avoid engaging in even the most minor ULPs so as to avoid imposition of a bargaining order pursuant to the Board’s new watered-down standard.

- Given the limited period available for filing an RM petition under Cemex, employers would be wise to consider in advance how they would respond to a union demand for recognition.

- Finally, employers can expect that union elections conducted after December 26, 2023 will proceed on a much faster track than they do now.

Contacts

Insights

Client Alert | 3 min read | 02.27.26

On February 17, 2026, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a complaint against Coca-Cola Beverages Northeast, Inc., in the United States District Court for the District of New Hampshire, alleging that the company violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII) by conducting an event limited to female employees. The EEOC’s lawsuit is one of several recent actions from the EEOC in furtherance of its efforts to end what it refers to as “unlawful DEI-motivated race and sex discrimination.” See EEOC and Justice Department Warn Against Unlawful DEI-Related Discrimination | U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Client Alert | 6 min read | 02.27.26

Client Alert | 4 min read | 02.27.26

New Jersey Expands FLA Protections Effective July 2026: What Employers Need to Know

Client Alert | 3 min read | 02.26.26