New U.S. Department of Defense Policy Imposes Security Reviews for Universities and Labs Engaging in Fundamental Research

What You Need to Know

Key takeaway #1

The U.S. Department of Defense identified a series of Chinese, Russian, and Iranian institutions and universities that have elevated risks. All universities and labs should ensure their restricted party screening providers screen for entities on this list going forward.

Key takeaway #2

Just because a university or research laboratory complies with U.S. export controls on the basis of fundamental research does not mean it will comply with U.S. Department of Defense obligations.

Key takeaway #3

Where a university or research lab initially files its patents has become relevant, and filing any patents outside of the United States (and in particular in China or Russia) for items that are the result of U.S. funded research can result in future risk.

Key takeaway #4

The application for fundamental research grants is still based on technical merit. The security considerations only apply once a proposing institution is selected.

Key takeaway #5

This is not a singular process across the entire U.S. Department of Defense; each agency or department may have processes that vary slightly depending on the potential risks so it will be important for universities and labs to monitor implementation on a continuous basis.

Client Alert | 30 min read | 07.11.23

Overview

Last week, the U.S. Department of Defense (“DoD”) issued a memorandum explaining new requirements in its efforts to “Counter[] Unwanted Foreign Influence in Department-Funded Research at Institutions of Higher Education” (the “Memorandum”). The Memorandum discusses DoD’s new processes to review proposals from higher education institutions for fundamental research opportunities, with a focus on security threats posed by China, Russia, and other malign actors.

The security reviews focus on proposing institution’s relationships and the role and relationships of all covered individuals (i.e., those individuals who contribute significantly to the design and/or execution of the fundamental research project being considered, and who are essential to the success of the project). It also makes use of a variety of preexisting regimes the U.S. Government (“USG”) has already implemented, including research protocols and standards and export and other restricted party lists.

Finally, for universities and research laboratories that rely on funding support from DoD for fundamental research activities, the Memorandum puts those institutions on notice that touchpoints with foreign talent recruitment programs; China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea; and U.S. export and sanctions lists, even if all touchpoints are legally authorized, could mean a denial for future funding applications.

View from Washington

Increasing Concerns About Foreign Talent Recruitment Programs

In recent years, the USG has adopted a whole of government approach to limit foreign influence and protect and foster U.S. technological superiority and human talent. For example, the U.S. Department of Justice (“DoJ”) and U.S. Department of Commerce (“Commerce”) have developed a Disruptive Technology Strike Force to identify and prevent theft of U.S. technology by illicit actors and enhanced U.S. export controls, with more restrictions on cloud computing reportedly forthcoming.

One aspect of this has been to mitigate the risk posed by foreign talent recruitment programs (“FTRP”). FTRPs are programs by governments (other than the United States) to recruit professionals and students in the United States (regardless of citizenship status or national origin) for the purposes of acquiring knowledge and technology for the recruiting government’s economic or military aims. The governments recruit individuals by offering financial and professional incentives and may seek to relocate them to the recruiting county. The USG is most concerned when these efforts come from a Foreign Country of Concern (“FCOC”) (currently defined to include China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia) and focus on individuals with a nexus to technologies critical to U.S. national security, such as aerospace engineering and artificial intelligence.

Congressional and Executive Action to Restrict Impacts of Foreign Talent Recruitment Programs

Efforts to mitigate the national security risks emanating from FTRPs have originated from both Congress and the President. In 2018, Congress included provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2019 (“NDAA FY19”) that called on the Secretary of Defense to protect U.S. research from foreign interference (Sec. 1286) and forbid DoD funding from going to Chinese language programs at U.S. universities with “Confucius Institutes” (Sec. 1091).[1] Confucius Institutes are cultural institutes funded by China and are alleged to promote Chinese influence. Congress went one step further and in the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2021 (“NDAA FY21”) included a requirement prohibiting any DoD funds from going to a university hosting a Confucius Institute without a waiver from the Secretary of Defense (Sec. 1062).[2]

Further, Congress included a provision in the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (“CHIPS Act”) (Sec. 10632)[3] that underscored the USG’s continued dedication to these efforts by seeking to prevent federal research agencies from giving contract awards to individuals aligned with “malign” foreign talent recruitment programs (“MFTRP”).[4]

With regards to the Executive, in January of 2021, days before President Biden was inaugurated, then-President Trump released National Security Presidential Memorandum – 33 (“NSPM-33”).[5] NSPM-33 directed the attention of executive departments and agencies to protect USG-supported “Research and Development” and called for procedures like disclosure requirements and clear consequences for violations. While the Biden Administration withdrew a number of Trump-era initiatives, NSPM-33 remained. Guidance on implementing NSPM-33 followed in 2022, highlighting 15 specific implementation requirements.

What does this Memorandum Do?

How Security Review Processes Will be Structured

The Memorandum, signed by the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (“USD(R&E)”), outlines a new DoD policy which requires all DoD Components (i.e., all DoD agencies and military departments) to develop a risk-based security review process for all fundamental research projects selected by the DoD Component for a funding award. Each DoD Component can develop their own security review of the fundamental research projects, but it must meet certain standards including:

- Employ the latest iteration of Appendix B (“Fundamental Research Review Template”) of the Science and Technology (“S&T”) Protection Guide, to ensure that the research project is truly considered fundamental research;

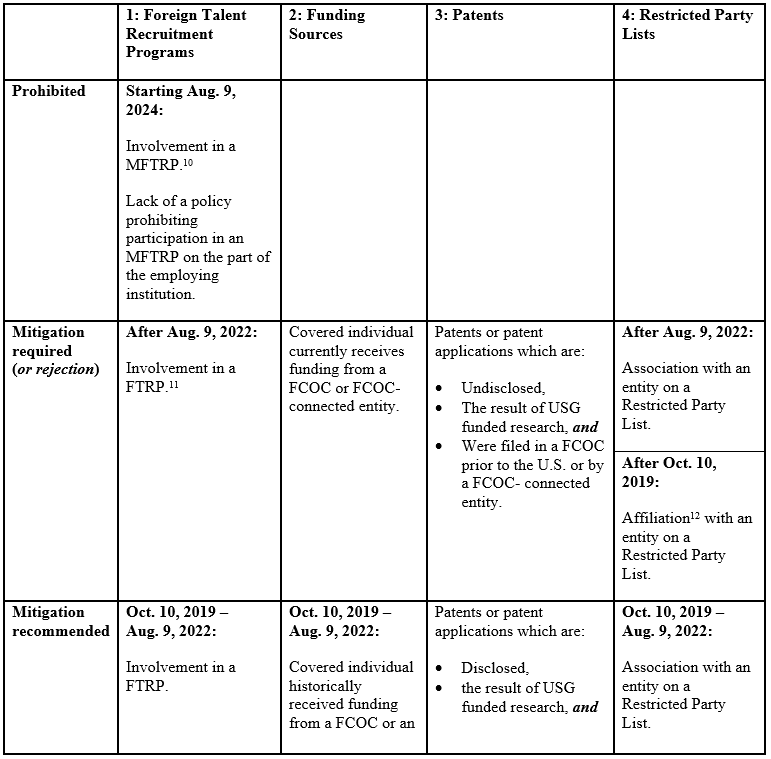

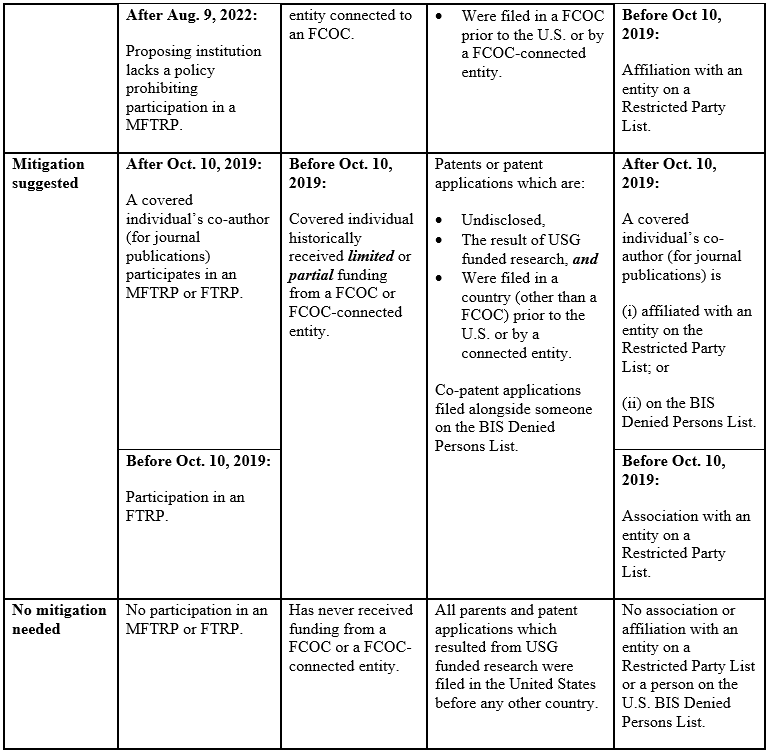

- Be consistent with the “DoD Component Decision Matrix to Inform Fundamental Research Proposal Mitigation Decisions” included in the Memorandum (see below an abbreviated version);

- Use disclosures and Standard Form 424 for all covered individuals in the research proposal to include the necessary and relevant information;

- Conduct an annual review of projects using the Research Performance Profess Report (“RPPR”), which is already mandated that federal agencies use through prior executive action; and

- Institute policies for how to determine what mitigation is necessary to ensure the appropriate levels of security.

At the same time, the Memorandum emphasizes the need to not discourage international collaboration, to promote efficiency while ensuring a secure review, and to ensure there is no delay in issuing the award.

Requirement to Mitigate Research Security Risk

In order to mitigate research security risks, the Memorandum requires each DoD Component to develop strategies and mechanisms to mitigate potential risk including, but not limited to, requiring the proposing institution to:

- Require covered individuals to complete insider risk awareness training;

- Require increased frequency of reporting of the covered individuals through the RPPR,

- Provide the DoD with a covered individual’s contract for review and clarify any risky relationships or associations. Associations can include any academic, professional, or institutional appointments or positions with a foreign government or foreign government-connected entity where no monetary reward, non-monetary reward, or other quid-pro-quo is involved, and

- Take specific actions regarding individuals considered a security risk or who are in “problematic” positions by either removing them from fundamental research project proposals or to resign from positions.

What Happens When a Fundamental Research Project Proposal is Rejected on Security Grounds

The Memorandum also spells out the required policies for when a fundamental research project proposal is rejected because the security risks cannot be mitigated or the risk is “unacceptable.” The DoD Component must issue a rejection letter to the proposing institution explaining the reasoning, with a copy sent to OUSD(R&E) who will share the findings with other DoD Components.

The proposing institution can challenge a rejection by referring to OUSD(R&E) for mediation. If OUSD(R&E) determines that the review was not conducted or analyzed on the basis of the factors described in the Memorandum, it can change the outcome.

DoD Components Will Coordinate for Consistent Positions

Finally, the Memorandum aims to ensure consistent review processes amongst the Federal agencies and DoD Components. To achieve consistency, the Memorandum instructs DoD Components to coordinate with OUSD(R&E), conduct spot checks of covered individuals and security reviews, and provide summaries of security reviews to OUSD(R&E). The policy also provides a series of steps that can be taken if there is a challenge to a research project rejection or an inconsistency amongst DoD components or Federal agencies.

Factors for Consideration

The Memorandum included a matrix to help research institutions understand the risks DoD assigns to fundamental research proposals, with a focus on four factors: nexuses to FTRPs; funding sources; locations of patents filings from other USG-supported research; and nexuses to certain identified restricted party lists. “Restricted Party Lists” include (i) Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) Entity List,[6] (ii) the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Chinese Military Industrial Complex Companies (“CMIC”) List,[7] (iii) the DoD’s Chinese Military Companies (“CMC”) List,[8] and (iv) any entities identified in the final pages of the Memorandum.[9]

Some of the factors are only applicable for certain dates, identified below as well.

Confucius Institute Prohibitions Enacted

The Memorandum further confirmed that beginning in fiscal year 2024, no higher education institution can receive funding from DoD if it hosts a “Confucius Institute,” unless the Secretary of Defense issues a waiver. As described above, a Confucius Institute is a cultural institute funded by the Chinese Government. Notably, a cultural organization does not need to be named a “Confucius Institute” to be deemed one.

We would like to thank Jasmine Masri and Riley Flewelling for their contribution to this alert.

[1] John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, H.R. 5515, 115th Cong. §§ 1091, 1286 (2017-2018).

[2] William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, H.R. 6395, 116th Cong. § 1062 (2019-2020) [hereinafter NDAA FY21].

[3] Chips and Science Act, H.R. 4346, 117th Cong. § 10632 (2021-2022).

[4] Id.

[5] Presidential Memorandum on United States Government-Supported Research and Development National Security Policy, (Jan. 14, 2021), available at https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-memorandum-united-states-government-supported-research-development-national-security-policy/.

[6] 15 C.F.R § 744.16, Supp No. 4 (2022).

[7] Exec. Order No. 14032, 86 Fed. Reg. 30145 (June 7, 2021) (published list can be found here https://www.treasury.gov/ofac/downloads/ccmc/nscmiclist.pdf).

[8] NDAA FY21 § 1260H (published list can be found here https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/05/2003091659/-1/-1/0/1260H%20COMPANIES.PDF).

[9] Dep’t of Def., Under Sec’y of Def. for Rsch. and Eng’g, Countering Unwanted Foreign Influence in Department-Funded Research at Institutions of Higher Education, at 18–21 (June 8, 2023).

[10] For the purposes of this matrix, an MFTRP is understood to be one which meets the requirements of the CHIPS Act in Sec. 10638(4)(A)(i)-(ix).

[11] For the purposes of this matrix, an FTRP is understood to be one which meets the requirements of the CHIPS Act in Sec. 10638(4)(A)(i)-(ix).

[12] “Affiliation” is more inclusive than “association” in that it includes “full-time, part-time, or voluntary” positions.

Contacts

Insights

Client Alert | 3 min read | 02.27.26

On February 17, 2026, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a complaint against Coca-Cola Beverages Northeast, Inc., in the United States District Court for the District of New Hampshire, alleging that the company violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII) by conducting an event limited to female employees. The EEOC’s lawsuit is one of several recent actions from the EEOC in furtherance of its efforts to end what it refers to as “unlawful DEI-motivated race and sex discrimination.” See EEOC and Justice Department Warn Against Unlawful DEI-Related Discrimination | U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Client Alert | 6 min read | 02.27.26

Client Alert | 4 min read | 02.27.26

New Jersey Expands FLA Protections Effective July 2026: What Employers Need to Know

Client Alert | 3 min read | 02.26.26