Intellectual Property - Time to Play Offense

Publication | 01.19.16

When the number of patent litigation filings declined in 2014, after four years of sharp increases, it raised hopes that recent changes to patent practice instituted by Congress might, in fact, be working to stem the tide of frivolous district court lawsuits.

These changes included the creation of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

But the numbers went back up in 2015, based on a surge of filings by non-practicing entities (NPEs), and these filings were on pace to set a new record by year’s end.

NPEs are not the only ones getting in on the action. Recently, more traditional patent owners have been instituting patent litigation more frequently as they seek to maximize profits from their patent portfolios. “Even for companies that have acquired patents for the purpose of using them defensively—i.e., to keep from getting sued—there’s a pressure to monetize those assets as much as possible,” says Michael Jacobs, vice-chair of Crowell & Moring’s Intellectual Property Group. “Many of these companies have spent millions developing these portfolios, and there’s an increasing sense that they should look toward playing more offense.”

With an increasing caseload, says Jacobs, both the PTAB and the federal courts will continue to adjust how to best handle patent disputes as they strive for that elusive balance between encouraging innovation by protecting patent rights while discouraging abuses of the patent system.

PTAB: STILL IN FLUX

After three full years of inter partes reviews (IPRs) at the PTAB, many questions regarding how the new venue for challenging patents would operate have been settled. Still some issues remain in flux. Jacobs, who has handled many cases before the PTAB and its predecessor (the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences), says its judges have held firm to the promise of limited discovery in IPRs consistent with the PTAB’s mission of being cheaper and quicker than district court litigation.

In recent months, however, the PTAB has shown a greater willingness to allow patent holders to amend their patent claims in IPRs—and therefore make them more likely to withstand challenges. While the PTAB has still only granted a patent holder’s motion to amend a handful of times in its three-year history, it did indicate in two 2015 decisions that it might be lowering the bar.

That easing of restrictions on claim amendments may be in response to criticism that the PTAB has been too hard on patent holders, Jacobs says. For example, in a 2013 speech, Randall Rader, then-chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, referred to the PTAB as a “death squad” for patents.

Jacobs believes the criticism is not entirely fair and suggests that it may be partly the result of the PTAB’s record of overturning software patents. He points out that both the PTAB and federal courts are more likely to reject software patents under the new patent-eligibility standards set by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 2014 Alice v. CLS Bank decision.

In June 2015, the Federal Circuit for the first time reversed a PTAB ruling in an IPR that a claim was unpatentable, but it has generally given PTAB judges broad deference. Jacobs predicts that this is likely to continue.

THE COURTS: LETTING PTAB HAVE ITS SAY

According to the USPTO, between 80 and 90 percent of the IPRs before the PTAB are directed to patents involved in litigation in U.S. district courts. In fact, it is a common defense strategy for a party accused of infringement to file a petition for an IPR in an effort to have the disputed patent overturned, says Jacobs. USPTO statistics indicate that in more than half of all cases, district court judges grant a stay to let the PTAB make its ruling on patentability first.

Whether district court litigation is stayed by the district court judge pending the outcome of the PTAB review depends on several factors, including where the suit has been filed, Jacobs says. If the litigation has been filed in a district that is known for maintaining a speedy pace, such as the Eastern District of Virginia, a stay may be less likely than in districts with longer timelines.

The impact of some recent amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (effective on December 1, 2015) could help streamline the patent litigation process, as will likely become clearer this year, Jacobs notes. One amendment is aimed at reducing the costs and duration of complex litigation by requiring the court and litigants to consider “proportionality” when deciding the permissible scope of discovery.

Another amendment eliminates complaints based on Form 18 in the Federal Rules, which has effectively allowed patent-owner plaintiffs to file complaints that provide little specificity to defendants. Jacobs, who represents both defendants and plaintiffs in patent cases, says that enhanced pleading requirements are a welcome development.

“IP litigation is among the most complex and costly types of litigation,” he says. “If you’re going to bring suit, you need to at least have done your homework first. Getting rid of Form 18 is a great start in that regard.”

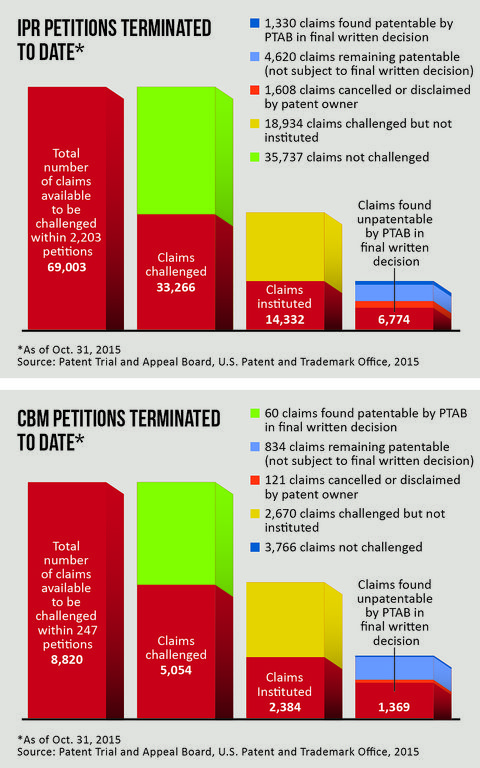

[TOP: Of the claims to be challenged through IPR petitions, nearly half—48.2%—were challenged, and 43% of those claims were instituted. The PTAB found 47.3% of those to be unpatentable.

BOTTOM: Of the claims to be challenged through CBM (covered business method) petitions, 57.3% were challenged and 47% of those were instituted. The PTAB found 5.4% of those to be unpatentable.]

[PDF Download: 2016

|

|

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | May 25-27, 2008

“ISI mitigation using bit-edge equalization in high-speed backplane data transmission,” in IEEE International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems (ICCCAS 2008), pp. 589 - 593.

Publication | 04.18.24

Publication | 04.16.24

Rochester, NY, Diocese's Creditors To Mull Rival Ch. 11 Plans