Government Contracts - More Protests, New Battlegrounds

Publication | 01.19.16

For federal contractors, protests against contract awards continue to be an increasingly familiar part of doing business—and if anything, those protests are becoming more vigorous.

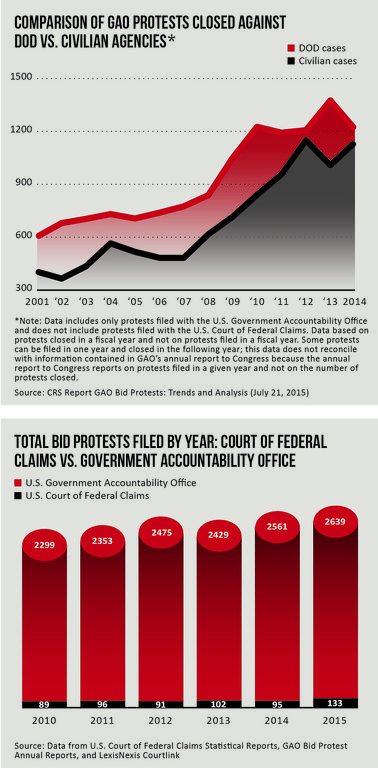

"Government agency budgets continue to be constricted, and that is increasing the competition for available dollars," says Lorraine Campos, a partner in Crowell & Moring's Government Contracts Group. "Thus we've seen an uptick in the number of bid protests being entered by contractors." According to a report from the Congressional Research Service, total government spending (adjusted for inflation) fell 25 percent between 2008 and 2014, while the total number of protests increased 45 percent. What's more, an increasing percentage of those protests now appear to involve contracts awarded by civilian agencies. "While bid protests have traditionally tended to involve military contractors, we're now seeing more from commercial or civilian contractors," she says.

In some cases, contractors are becoming more involved in the government's handling of protests and proactively intervening in the proceedings. "In the past, the winning party would just sit back and let the government and the losing party duke it out," says Campos. "Now, winners are more likely to help the government develop its case, especially when there is a massive record involved."

Campos says that there are now more bid protests targeting multiple award schedules. Under these schedules, the General Services Administration (GSA) selects vendors and negotiates contract prices, terms, and conditions for routine items. Then, agencies simply select the items they need from a catalogue, using individual task orders under the overarching contract, thus avoiding the need to renegotiate every purchase. However, budgets have prompted some agencies to begin asking for competitive bids for task-order purchases, meaning that the vendors already approved under the main contract have to compete once again. The structure of bidding at that level naturally opens the door to more protests.

THE CHANGING PROTEST LANDSCAPE

The procuring agency, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, and the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) can hear bid protests. However, for a variety of reasons, including the GAO's ability to stay the award of a contract, the GAO is often the forum of choice by contractors. Nevertheless, bid protests at the GAO are somewhat less likely to succeed today. From 2001 to 2008, the office sustained protests 22 percent of the time, according to the Congressional Research Service. By 2014, that sustain rate had dropped to 13 percent. Some of that decline may be due to agencies' willingness to take corrective action in response to protests, thereby resolving the issue before the GAO issues a decision. But the decline also suggests that fewer protests are succeeding on the merits.

For many contractors, losing a protest at the GAO is not the end of the story—and a growing number are finding that another venue is open to their arguments. "The U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which hears "appeals" of GAO decisions has the ability to revisit protests denied by the GAO—and the high-dollar, long-term awards are being vigorously protested there," says Campos. "This has effectively added an appellate process for unsuccessful protestors, giving them the proverbial second bite of the apple," she says. For contractors that win at the GAO, then, "it's important to understand that it may not be over, because the losing party could have an opportunity to bring issues regarding the agency's procurement activities up again at the court—and thus delay the contract award."

PROTESTS AS A DELAYING TACTIC

Whichever the venue, the growing competition for federal dollars is prompting some companies to go to great lengths to hold onto business—even if it's only a temporary gain. "A number of contractors appear to be using the bid protest as an intentional delaying mechanism," says Campos. Here, incumbent contractors are incentivized to file a protest even when they see little chance of winning.

"When a protest is filed at the GAO, in most cases a stay is issued and performance under the contract continues for the duration of the protest," says Campos. "So if an incumbent ultimately loses a contract award, by filing a protest with the GAO and obtaining a stay, the incumbent contractor will be granted several more months of performance during the pendency of the protest. So from their perspective, there is really nothing to lose—and significant profits to gain."

It is difficult to say with certainty how many protests are really just tactics for delay. But the issue is significant enough that in mid-2015 Congress raised it in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2016. The NDAA instructs the Department of Defense (DOD) to conduct a study to find out how protests and associated delays affect agency performance and how frequently protests are used simply to create delays.

Bid protests—and associated litigation—will continue to be a regular part of the government contracting landscape in the coming year. Agencies are still working with tight budgets, the intense competition for available dollars remains, and it seems clear that funding is not likely to increase in 2016. "This is an election year, and I doubt that budgets will be increased," Campos says. "So the number of bid protests, at the agency level, GAO, and the Court of Federal Claims, is likely to keep growing."

Top: Bid protests coming through the GAO continue to rise—and commercial contractors from outside the defense industry account for a growing percentage.

Bottom: A significant number of contractors are appealing protests to the Court of Federal Claims.

[PDF Download: 2016

|

|

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Insights

Publication | May 25-27, 2008

“ISI mitigation using bit-edge equalization in high-speed backplane data transmission,” in IEEE International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems (ICCCAS 2008), pp. 589 - 593.

Publication | 04.18.24

Publication | 04.16.24

Rochester, NY, Diocese's Creditors To Mull Rival Ch. 11 Plans